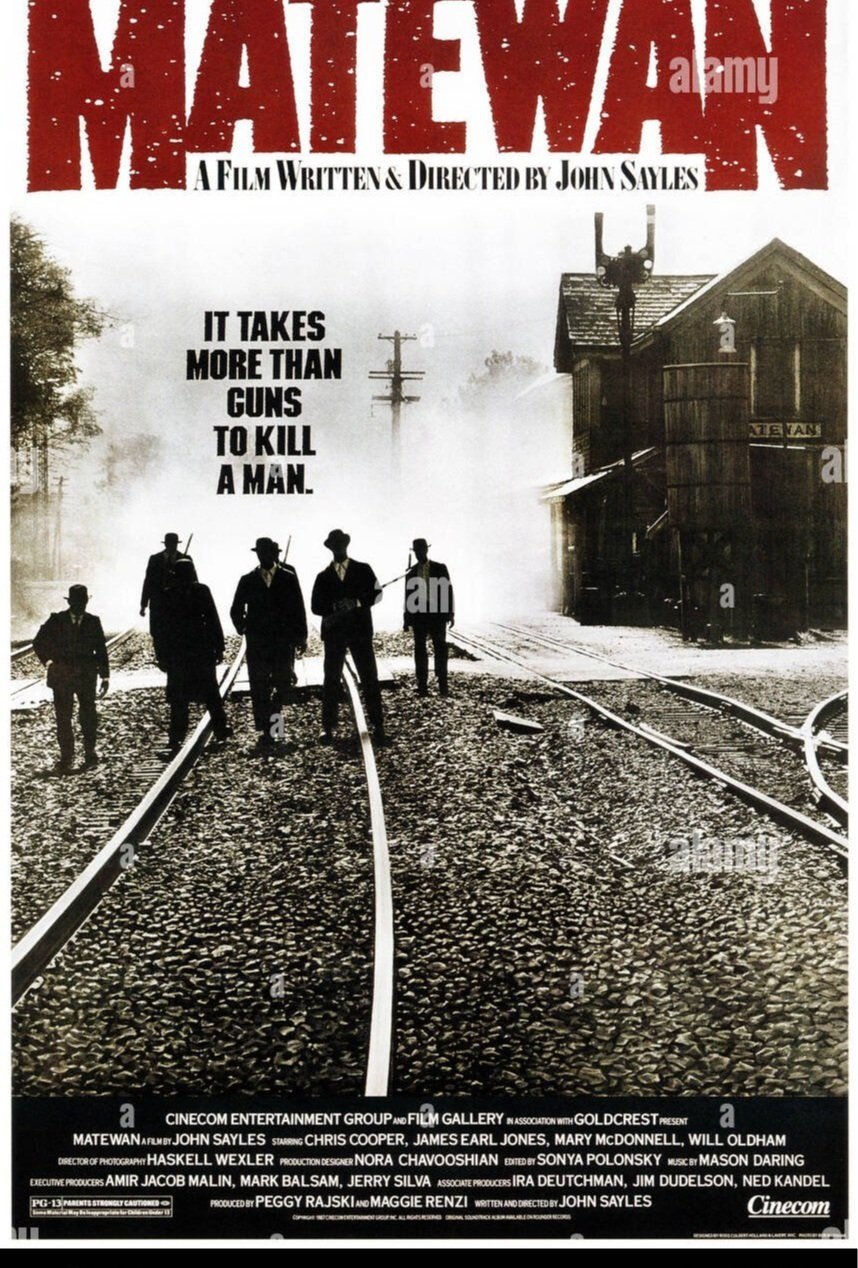

Episode 36: Matewan (1987)

(Guest: Fred B. Jacob)

Listen Anywhere You Stream

~

Listen Anywhere You Stream ~

Matewan (written and directed by John Sayles) dramatizes the events of the Battle of Matewan, a coal miners’ strike in 1920 in a small town in the hills of West Virginia. In the film, Joe Kenehan (Chris Cooper, in his film debut), an ex-Wobbly organizer for the United Mine Workers (also known as the “Wobblies”), arrives in Matewan, to organize miners against the Stone Mountain Coal Company. Kenehan and his supporters must battle the company’s use of scabs and outright violence, resist the complicity of law enforcement in the company’s tactics, and overcome the racism and xenophobia that helps divide the labor movement. Sayles’s film provides a window into the legal and social issues confronting the labor movement in the early twentieth century and into the Great Coalfield War of that period. I’m joined by Fred B. Jacob, Solicitor of the National Labor Relations Board and labor law professor at George Washington University Law School. Fred’s views on this podcast are solely his own and not those of the National Labor Relations Board or the U.S. Government.

30:08 Racial and ethnic tensions within the labor movement

39:29 What was law and who was law

46:40 The Battle of Blair Mountain

51:54: The Great Coalfield War to the National Labor Relations Act

56:59 Barbara Kopple’s Harlan County, USA

1:01:59 The power of the strike

0:00 Introduction

2:46 A miner’s life

7:44 The power of the mining companies

12:25 Law’s hostility to labor

19:01 Violence and the labor movement

25:33 Organizing the miners in Matewan

Timestamps

-

00;00;16;03 - 00;00;38;18

Jonathan Hafetz

Hi, I'm Jonathan Hafetz, and welcome to Law on Film, a podcast that looks at law through film and film through law. Our film today is made one. The 1987 movie, written and directed by John Sayles, that dramatizes the events of the Battle of Made One, a coal miners strike in 1920, in the small town in the hills of West Virginia.

00;00;38;25 - 00;01;00;26

Jonathan Hafetz

In the movie, Joe Carnahan, played by Chris Cooper in his film debut, a union organizer comes to meet one to organize the miners against the Stone Mountain Coal Company. Keenan and his supporters must battle the company's use of scabs and outright violence, resist the complicity of law enforcement, and the company's tactics, and overcome the racism and xenophobia that helps divide the labor movement.

00;01;00;29 - 00;01;25;01

Jonathan Hafetz

Sales. This film provides a window into the legal and social issues confronting the labor movement in the early 20th century, and into the Great Coalfield War of that period. For our discussion of mate one, I'm joined by Fred B Jacob, solicitor of the National Labor Relations Board and labor law professor at George Washington University Law School. Fred's views on this podcast are solely his own and not those of the NLRB or the US government.

00;01;25;04 - 00;01;29;20

Jonathan Hafetz

Fred, welcome back to Law and Film. It's great to have you on again to talk about made one.

00;01;29;23 - 00;01;39;11

Fred Jacob

Thank you, thank you. I'm so thrilled to be here and talk about May 1st and and delighted to be back. I feel like, you know, returning guest to The Tonight Show or something. It's really exciting, if only.

00;01;39;11 - 00;01;40;11

Movie Dialogue

But yeah, absolutely.

00;01;40;11 - 00;01;58;17

Jonathan Hafetz

I feel like that too. It's like we've got our rapport and we're we're ready to go and we've got such a great movie to talk about. Me. You know, I think it's one of John Sellers's best movies, and it just feels super fresh and relevant today when you watch it. I mean, it's a historical movie, but the way he draws the characters and the issues and it just really grabs it, grabs me.

00;01;58;22 - 00;02;19;07

Fred Jacob

And I think you're right, it's very relevant today, given the hot labor summer of last year, which triggered hot labor fall, and what we're seeing in the Gallup polls every year, Gallup produced a poll talking about how union disapproval is lower than it's been since the 1960s, and union approval is as high as it's been since the 1960s.

00;02;19;14 - 00;02;37;14

Fred Jacob

So we're really in a place where people are thinking about labor, and people are thinking about what it means to be part of a union. And certainly I know the National Labor Relations Board is seeing that as well with our case. And take. And so that's keeping us all very busy. But it makes this movie and others like it really relevant and fresh.

00;02;37;16 - 00;02;52;11

Jonathan Hafetz

So let's flashback to the made one, which is set in 1920, around 1920. What was it like working in the mines around that time? And there's a folk song that paints a picture of the hard life that it was.

00;02;52;13 - 00;03;40;05

Movie Dialogue

Miner's life is like a sailors on board a ship to the way I read there was a life in danger. Still keep to being brave. Was the rocks then falling daily perilous mining was always back. To keep your hands on the dollar and you're up on the sky.

00;03;40;08 - 00;04;02;18

Fred Jacob

And miner's life card says it all right there, right every day his life's in danger. Still he ventures, being brave. Keep your hand upon your wages and your eye upon the scale. Right. It's sort of a duel. Fear is every day having your life at danger and your pay stolen by corporate mine owners. So you ask, what was it like to work in the mines?

00;04;02;18 - 00;04;24;04

Fred Jacob

And I was trying to think about how to answer that question. I will give a lot of credit at the beginning of this podcast to an amazing book by James Green called The Devil Is There. The Devil Is Here in These Hills, which is a fascinating exploration of the battle to organize the mines, particularly in West Virginia. It's really incredibly informative.

00;04;24;04 - 00;04;45;23

Fred Jacob

And for anyone's interested in this area, they should pick it up and read it. But in answering your question, what was it like to work in the mines? I would say imagine the worst job you've ever had. You know, I was thinking, what's the worst job I've ever had? It was probably selling soda outside at an amusement park when I was in college, and multiply that by like a thousand times worse, right?

00;04;45;25 - 00;05;17;13

Fred Jacob

Working in a coal mine in the 1920s was a dangerous, desperate job. From a big picture standpoint, coal was incredibly important to the US economy. It was the single most important source of energy in the country. It fueled electricity, it fueled steelmaking, it fueled homes, it fueled businesses. And so every lump of coal that could be mined from a coal mine was incredibly important.

00;05;17;16 - 00;05;56;12

Fred Jacob

And as important as it was, it was also incredibly dangerous. So if you were a coal miner and coal miners often started in their early teens, their boys who were going into the mines all the way through, elderly men who were probably elderly at the age of 45, given the hard life they had. But you can imagine you're carving a hole into a mountainside to get this coal out, and they use this room and passageway form of extracting the coal where slowly blow these passageways through.

00;05;56;14 - 00;06;25;09

Fred Jacob

And using either railcar on a railway tracks that the miners built in their off time or mule, they would traverse these passageways, and then they would blow rooms using dynamite. So you'd have a room that would be blown in a tiny little room, like the most claustrophobic room you could possibly imagine. And in partnership, the miners would crawl into this room and then slowly put a iron needle into the wall.

00;06;25;11 - 00;06;48;18

Fred Jacob

Put some explosive into that on your needle, use a fuze, run out of the room shouting fire in the hole. Light the fuze and if they were lucky, the explosion would loosen a ton of coal, a little ton of coal that they could. Then, in this tiny, tiny space, chop up with their pick and their ax and then unload out of the mountain.

00;06;48;20 - 00;07;13;28

Fred Jacob

If they were unlucky, the entire roof could fall in. Coal dust could be ignited and set the entire room passageway, mountain on fire, or some other tragic happening could befall them. So it was extremely dangerous work. It was extremely delicate work because you needed the experience and knowing how to blow these holes. And they would do this 5 or 6 times a day in and out of the mountains.

00;07;14;01 - 00;07;38;23

Fred Jacob

They earned a pittance, $0.49 a ton for doing this. And the death rate in West Virginia was five miners for every thousand workers every year. Maybe that doesn't seem like a lot, but it was double the death rate of other collieries in Illinois and unionized states because West Virginia's laws were so lax. So 1920 is not the time you want to be working in a mine in West Virginia.

00;07;38;25 - 00;08;06;01

Fred Jacob

It's always been treacherous work, but it was particularly treacherous men. And then combining that. So as I was saying, you know, and as the sun miners Lifeguards says, you're afraid of for your life every day, and your economic life is under the yoke of the mine, completely in a futile state. When we talked last time about Norma Rae, we talked about the company towns in North Carolina that were textile mills in the 1970s at the time of Norma Rae.

00;08;06;04 - 00;08;29;07

Fred Jacob

But when we talk about the company towns of West Virginia in the 1920s, we're talking about a time where we didn't have interstate highways. There weren't as much telephone lines, didn't reach out to West Virginia, and they were truly isolated. And the towns were completely run and owned by the mine workers. And we are the mine owners. And we see this in May 1st.

00;08;29;10 - 00;08;55;05

Fred Jacob

Right. That amazing scene when the new workers, the black workers, show up at the beginning of the movie and they're given the lesson in the company store about what their life will be like now that they're mine workers and they're paid entirely in company scrip, not dollars. The company scrip has to be spent at the company store they live in company owned housing for which they pay rent through company scrip.

00;08;55;07 - 00;09;15;20

Fred Jacob

If they are fired, they have to leave company housing. These company towns. To the extent that there were churches, the churches were built by the company to the extent there were schools. The schools were built by the company to the extent that there was any infrastructure. Typically police stations, law, you know, government all run by the company down.

00;09;15;22 - 00;09;39;29

Fred Jacob

And then on top of it, all the guards who worked at these factories were not municipal guards that were employed by the city or the county or the state. They were company card that did not report to the governor or the mayor, but reported to the owner of the mine. So it was an extremely desperate life to be a miner in West Virginia, where you're eking out a living.

00;09;40;02 - 00;10;08;12

Fred Jacob

And to the extent you eked out a living, you were completely under the control of your bosses, the mine owners who owned those mines. And that's when the UMW tried to start organizing in the 1880s and organized throughout Appalachia and in the West, had success in the northern states. But West Virginia, as of the time of May 1st, was a huge holdout, and the miners there were battled it tooth and nail.

00;10;08;14 - 00;10;30;17

Jonathan Hafetz

You know, it's interesting when you say that about the power that the mines had, the miners had how disempowered the workers were, because I guess, unlike another industry, potentially, or if you think about unionizing today, your house, you didn't own your house or you didn't rent a house you had. No. So if you were, you know, if if you lost your job, you're fired or the company didn't want you there, you know, you lost your job.

00;10;30;24 - 00;10;33;28

Jonathan Hafetz

You were effectively rendered homeless, right? You were kicked out of your house.

00;10;34;01 - 00;10;55;08

Fred Jacob

Exactly. And we see that that's the sort of the dramatic throughline is at the Baldwin Phelps show up, and they want to evict the workers who have probably violated the yellow dog contracts. And by joining the union. And that's sort of the narrative throughline, is the attempt for the Baldwin Phelps to evict the workers, to successfully evict them eventually.

00;10;55;08 - 00;11;27;03

Fred Jacob

And they end up living in these tent camps. And your entire existence is completely at the whim of the company. And, you know, many employees ended up owing more money to the company than they earned. I mean, again, there's that great scene at the beginning where the company goes through this whole laundry list of not just how much they're gonna have to pay for rent, but how much they're going to have to pay for their tools, how much they're gonna have to pay to wash their tools, how much they're going to have to pay, you know, for their uniforms and so all the incidents of employment employees were required to pay for out of their

00;11;27;03 - 00;11;30;10

Fred Jacob

earnings and not in dollars, but in company scrip.

00;11;30;12 - 00;11;51;20

Movie Dialogue

These picks and shovels had to be considered a loan from the Stone Mountain Coal Company. That cost would be deducted from your first month's pay to shop, and provided by the company's $0.25 a month use of the wash house to $0.75 a month medical doctor provided by the company's $2 a month special procedures. Actually, the train ride here provided by the company will be deducted from your first month's pay.

00;11;51;27 - 00;12;16;05

Movie Dialogue

Pay will be issued as company scrip, redeemable for all goods and services at the Stone Mountain Company store. Purchases of any items available at the company store from outside merchants will result in firing without pay. Powder, fuzes, labs, headgear all appropriate clothing will be available at the company's store, and Stone mountain will generously advance. You will not supply these items.

00;12;16;10 - 00;12;17;27

Movie Dialogue

They're meant to be deducted.

00;12;17;29 - 00;12;25;08

Fred Jacob

So mean. It really was a futile experience and that was legal until the mid 20th century.

00;12;25;11 - 00;12;49;09

Jonathan Hafetz

So we talk about the law and there's a question of whose side is the law on Baldwin Phelps. That's the private detectives, investigators who work for the mine owners. Are you there to kind of suppress the labor organizing, including the rise of violence? What they seem to be doing is extralegal, but it's unclear where the law stands and who side the law is on.

00;12;49;09 - 00;12;56;03

Jonathan Hafetz

So how do law help or hinder labor at the time? And I take it it's mostly a hinder.

00;12;56;06 - 00;13;20;13

Fred Jacob

It is mostly a hinder. And to answer your question, were the Baldwin Phelps extra legal? And I think we'll talk about this more. But this was a company town, you know, who is the government in this town? Is it the company or is it the municipal government that Mayor Testament runs and Sheriff Hatfield run? Or is it the company that essentially owns all of Mingo County?

00;13;20;15 - 00;13;40;28

Fred Jacob

Law, as a general matter at this time was, as you said, a hindrance? And it's funny, when we first started talking about this movie, I was thinking, oh, it'll be really interesting. And someone who has spent many, many years thinking about the National Labor Relations Act to talk about what it was like to try to organize in a world where there was an absence of law.

00;13;41;00 - 00;13;57;18

Fred Jacob

And then I started thinking about it and watching the movie and thinking about my labor history. You know what we teach on the very first day of labor law and we go through, you know, the history of labor law and how we got to where we are. And I realized there wasn't an absence of law. There was a very definite presence of the law.

00;13;57;21 - 00;14;25;15

Fred Jacob

It was just the law that showed a tremendous and marked hostility to labor. And so what we saw was almost a century from the time unions first started to appear in the early 19th century through the New Deal era of continued and regular and sustained hostility and oppression towards labor organizing. And it typically ended up in three buckets.

00;14;25;15 - 00;14;55;06

Fred Jacob

And I would say these three buckets effectively work together to deprive unions and workers of any civil ability to vindicate their right to organize. So even to the extent that they had some nominal First Amendment right to organize, they had no ability to vindicate it beyond economic power. And to the extent that fails, violence. So the first big bucket was conspiracy laws, civil and criminal conspiracy laws.

00;14;55;08 - 00;15;31;08

Fred Jacob

From the time unions first showed up in the early 19th century, employers accused them of entering into conspiracies to obstruct their business. These laws had legs, and throughout most of the 19th century, employers were able to obtain injunctions from state courts and federal courts under civil conspiracy laws, asserting that when a union, for example, picketed outside a company, an employer because they paid nonunion wages or hired nonunion workers, that that was a civil conspiracy to interfere with their business relationships.

00;15;31;08 - 00;15;55;11

Fred Jacob

And there's a famous case out of the Supreme Court of Massachusetts called on the Gunter, where the Supreme Court of Massachusetts found that a perfectly legitimate claim to Brown and then soon to be Justice Holmes dissented, suggesting that employees had as much right to combine and to use persuasion to convince others to join a union, or to convince employers to pay union wages.

00;15;55;13 - 00;16;20;28

Fred Jacob

As an employer does, to combine for capital. But conspiracy laws were a huge tool that employers used. Secondly, employers. Once the Sherman Antitrust Act was passed, the Sherman Antitrust Act was used against unions as a restraint of trade, and federal courts repeatedly granted injunctions and enjoined union activity as restraints of trade. Supreme court affirmed that in a case called Lawlor below.

00;16;20;28 - 00;16;41;12

Fred Jacob

In 1908, Congress passed the Clayton Act to try to override it legislatively. They specifically said in the Clayton Act that labor is not a commodity or an article of commerce. And the Supreme Court said, yeah, we don't care about what you said. It's still a violation to engage in a secondary boycott or to try to encourage people to boycott businesses for labor activity.

00;16;41;17 - 00;17;05;18

Fred Jacob

And it wasn't until the 1930s where Congress was able to pass legislation that was effective to strip, literally strip, the federal courts of jurisdiction, to hear any case involving labor injunctions in the North LaGuardia act. But before Congress did that, the last tool in the courts toolbox that they used to strike down labor and hurt labor was Lochner.

00;17;05;21 - 00;17;30;25

Fred Jacob

We're talking a lot about Lochner now. It feels like we're having a little bit of a Lochner redo these days. And the Lochner case was used by the Supreme Court in the 19 tens to basically make it unconstitutional for a state to ban yellow dog contracts. Now, yellow dog contracts are contracts in which an employer required an employee to give up their right to join a union as a condition of employment.

00;17;30;27 - 00;17;55;15

Fred Jacob

They were called yellow dog contracts because I think it was in a miners actually of miners magazine. They said only signing one of these contracts would bring you to the status of a yellow dog. And so they became known as yellow dog contracts. And so Supreme Court said that Lochner gives businesses a constitutional right under the Fifth and 14th Amendment to enter into contracts with employees without interference.

00;17;55;17 - 00;18;17;20

Fred Jacob

And attempts to ban Yellow Dog contracts were unconstitutional by both states and the federal government. Within the federal government had attempted to step in in the railroad industry and banned them. But what that did, most frighteningly for unions, was that it essentially open up the door to the federal courts as a means for seeking injunctions under the diversity laws.

00;18;17;23 - 00;18;49;16

Fred Jacob

In any time that a union was attempting to engage in some sort of economic action to interfere with their, quote unquote, yellow dog contracts, the employer could go to federal court and seek an injunction, and the federal courts granted them. And by enjoining any sort of way I look at it by enjoining all of these, any sort of peaceful protest and what we're talking about, a protest like picketing outside of business by just merely encouraging people to join a union once they had signed a yellow dog contract, these were all enjoined.

00;18;49;24 - 00;19;05;00

Fred Jacob

And once you start to enjoying this action, you're leaving labor. As I said earlier, with fewer and fewer tools that are peaceful to try to persuade workers to join. And when you don't have peaceful tools, it takes the only path that it could take.

00;19;05;02 - 00;19;24;25

Jonathan Hafetz

And that's the path of the labor violence, right, that we see in the movie. So you have not an absence of law, an absence of law, recognizing the right of labor to organize. And so we see violence at multiple junctions in the film, and we see violence near the opening. We have to see violence between the union and what they see as scabs brought in.

00;19;24;25 - 00;19;46;26

Jonathan Hafetz

You know, they take their jobs with the scabs at work. African-American don't know why they're being brought in for that particular purpose. A main area of violence is the Baldwin felt group just coming in, trying to push the workers off their land and engaging in violence against union leaders. So we see a lot of the violence. So what role did violence play or how big a role did violence play in subverting the labor movement?

00;19;46;28 - 00;20;20;27

Fred Jacob

Violence was very common in the late 19th century and early 20th century. In labor, I almost said it was ubiquitous, and I don't know if it's fair to say it was ubiquitous, but if you read a labor history, labor history is replete with instances of pretty significant violence, and sometimes it's localized. And we can look at the Haymarket massacre in Chicago in 1886, where there was a protest for the eight hour day, and somebody still to this day unknown, who threw a homemade bomb into the protest.

00;20;21;00 - 00;20;58;23

Fred Jacob

And it set off a huge police action. And the police ended up shooting numerous protesters. And there was violence and return protesters and workers and police officers died that day. And that was May 1st, 1886. Why we commemorate May 1st is International Labor Day and May day, but that's sort of a one off instance. And I think some of these instances are due to the fact that labor at that time was as political as it was economic, and there were challenges to the existing system of capitalism and of American democracy that people viewed as extremely threatening.

00;20;58;27 - 00;21;23;16

Fred Jacob

And so it wasn't just about dollars and cents entirely. You know, when you're challenging the status quo, sometimes tempers go up. And I think a lot of the violence was due to the nature of labor organizing, particularly in the 19th century. But, you know, certainly by the time you're in the 20th century, the violence we're seeing, I think, is really directly related to the fact that unions are not able to organize.

00;21;23;16 - 00;21;53;05

Fred Jacob

And one of the huge issues that we see in this movie, West Virginia miners were not the only miners to suffer violence during their organizing. Shortly before May 1st, and the events that happened in Maitland in 1914, there was a Ludlow Massacre in Colorado, where the Baltimore developed, went out at the behest or at the employ of mine owners, and ended up machine gunning workers, their wives, and their children who were living in tent camps because they were evicted from their company town.

00;21;53;07 - 00;22;25;29

Fred Jacob

We saw general strikes throughout the nation that were violent, and then there was a huge West Virginia coal strike in 1912 that was called the Battle of Paint Creek. And that was a precursor to what we see at Maitland. Similar issues, though, over organizing, over attempting to build a union where mine workers were unable to do so because of mine owners intransigence, their hiring of private guards, and their attempt to try to press their demands in the absence of any legal right to do so.

00;22;26;01 - 00;22;50;00

Fred Jacob

So again, when you have no personal autonomy or legal outlets, everything filters towards violence. And at least James Greene talks in this book about West Virginia that I mean, the title speaks for itself. The devil is here in these hills, that there was also something to the West Virginia culture. You know, this is the land of the Hatfields and the McCoys, which everybody in this book is named Hatfield.

00;22;50;02 - 00;23;00;23

Fred Jacob

I mean, there are lots of Hatfields and McCoys, and there is a tradition of mountaineering and self-determination and autonomy. We see that with the hill folk who come into that scene in the movie. Right.

00;23;00;25 - 00;23;16;07

Jonathan Hafetz

That's a great scene when there's the confrontation between Baldwin Phelps and Sid Hatfield. Right. We'll talk about them a little as the police chief who's protecting allegiance to the mineworkers. And it looks like it's going to boil into a conflict. And then people stumble in from the woods, right? Yeah. They lived off the great even for 1920.

00;23;16;09 - 00;23;35;06

Fred Jacob

Yeah, exactly. There was off the grid as you can get. And I think in the movie they talk about how these are folks whose land was stolen by the miner. You know, they were forced to sign contracts or they signed contracts and they probably weren't even semi-literate. And, you know, ended up giving up all their rights to the mine and to their property.

00;23;35;08 - 00;23;42;24

Fred Jacob

So they were not big fans of the mine either, but they were kind of not involved in the fight because they weren't miners. They're just kind of living off the land.

00;23;42;27 - 00;23;59;28

Jonathan Hafetz

Right? They're disturbed by the commotion. It's getting in the way of their hunting activity. And then there's a great there's that great line of dialog between, main Baldwinsville guys and one of these, you know, West Virginia individuals who comes in from the woods where, you know, he asks them about his gun.

00;24;00;02 - 00;24;19;12

Movie Dialogue

He was hunting. You folks are making an awful lot of commotion. He scattered all the game away. This machine appeared at last night, too. It's an offense to the air. Hold it! Pops, you're talking to the law here? He asks you anything?

00;24;19;15 - 00;24;22;25

Jonathan Hafetz

Pointing his old rifle at the Baldwin Phelps agent.

00;24;22;27 - 00;24;41;15

Movie Dialogue

Where'd you get that thing, pal? Spanish war now, or between the states? You're all getting this machine and get back into town where you belong. Ain't for one long way out of here. And that's a law in nature.

00;24;41;17 - 00;24;48;21

Jonathan Hafetz

So it does show, as you're seeing kind of all the different, the interesting layers that go on in West Virginia, which doesn't really seem a place apart.

00;24;48;23 - 00;25;10;14

Fred Jacob

Yeah, exactly. I mean, we're talking about Mingo County, as I was mentioning earlier, you know, like it was hours and hours and hours from major cities. I mean, truly isolated in the tiny southwest corner of the state. There is if you ever want to go on our field trip, we can go to the West Virginia mine War Museum, which is actually inmate one, and also the great website if you want to learn a lot about this.

00;25;10;16 - 00;25;11;13

Jonathan Hafetz

I love that.

00;25;11;16 - 00;25;33;01

Fred Jacob

Yeah, it looks amazing. And I thought, I live in Washington DC not too far away, but it's a seven hour drive from Washington DC now. So, you know, really the southwest corner of the state where people took care of their own business. And that is truly, as you said, layered on top of the legal and the economic and the political that we're talking about.

00;25;33;03 - 00;26;01;11

Jonathan Hafetz

And so into this situation. Right. The beginning of the film comes jogging a hand to Chris Cooper character who's in next, International Workers of the world or who aka wobbly organizer, who comes in to try to organize or help organize the United Mine Workers union, or help the United Mine Workers Union organize the labor force and make one.

00;26;01;15 - 00;26;09;06

Jonathan Hafetz

There's a great line of dialog where the union folks test Joe Keenan to see if he's legit. They test his labor knowledge.

00;26;09;09 - 00;26;34;14

Movie Dialogue

Claims he's a fellow of the unions. His. Can you prove it? Don't take nothing. Have a card printed up. I guess you just have to trust me, he wrote down here. Jack London, where is Joe Hill? Buried all over the world. I scattered his ashes, which I his big Bill Haywood mission. That's right. One at Frank little died Butte, Montana.

00;26;34;14 - 00;26;43;19

Movie Dialogue

They hung him from a railroad trestle. Oh, you know your stuff? I was with the Wobblies. Me too. Back when it medicine.

00;26;43;22 - 00;26;49;22

Jonathan Hafetz

Who are the Wobblies and why were they important to unionize him in in 1922?

00;26;49;22 - 00;27;30;26

Fred Jacob

What's interesting is that the Wobblies were less important to unionism. By 1920. I was thinking about it as we were preparing for this podcast and the Wobblies were a huge, really important labor organization that formed in the late 1900s and were really prevalent through and around this time, but were fading out by this time. And they believed, as I think C lively says at one point, kind of sarcastically and, you know, one big union, the idea that all workers should be united together and they all were bound by their status as laborers in the world.

00;27;30;29 - 00;27;59;17

Fred Jacob

And they were, as I was mentioning earlier, there were some unions that really viewed their role as changing the world. And the Wobblies were were one of those unions. And I do love that scene, too. With the trivia quiz we were talking about, which I did big Bill Hayward lose. And, you know, these were huge personalities in the labor movement who organized thousands and thousands and thousands of workers across occupational lines, across industry lines.

00;27;59;19 - 00;28;24;00

Fred Jacob

And that was a revolutionary way of thinking about union organizing at the time, because prior to that, union organizing was really focused on organizing craft by craft. So, you know, you'd have your your core donors or your shoemakers or your car makers or your printers and probably even further subdivided by, you know, people who work in printing to your typesetter and your print masters.

00;28;24;02 - 00;29;02;01

Fred Jacob

But the Wobblies wanted to organize everyone, and I think they ended up fading away as the mine workers and the AFL CIO or the AFL. At the time, there was no CIO. So the American Federation of Labor, led by Samuel Gompers, and the mine workers led by John Lewis, really started to focus on business unionism instead of political unionism like folk, and sort of accepting the premise that we live in a capitalist society, but recognizing that there is a place for workers to organize and organize to get the best deal possible, that they are entitled to the fruits of their labor.

00;29;02;01 - 00;29;21;17

Fred Jacob

Within the context of the society, we have. So I think it's interesting that, like, by the time Joe Carnahan shows up, he's out of step with the mine workers who, at the very least, the mine workers in Maitland who are pretty willing to use violence as a tool for organizing because he's a pacifist. He went to jail as a conscientious objector.

00;29;21;29 - 00;29;43;16

Fred Jacob

And there's a wonderful scene where he talks about seeing the Mennonites who were conscientious objectors. And he's been out of step, I think, as a probably as a one big union proponent versus what we would now know as business unionism. Again, it's another theme in this movie, right, of pragmatism versus idealism, like, what are we trying to do here?

00;29;43;19 - 00;30;09;23

Fred Jacob

And Joe is constantly the voice of idealism, like he wants to build an ideal society where workers get what they deserve and are treated with respect, and to do it without violence. They do it with a nonviolent strike activity and nothing else. And that's a constant tension in the movie, right? Like, how do you make that happen in a world where you have no rights, in a world where you have no power.

00;30;09;25 - 00;30;32;28

Jonathan Hafetz

And where the owners are using violence, they're employing Baldwin Felts, so you strike back violence ends with violence. And we well, we'll talk a little later in Barbara Koppel's 1976 documentary. But even then, years later, that theme is still there, right? Violent. And the business unions and I think that's the UMW, right. United Mine Workers stand becomes the force will become the force for organizing in the minds.

00;30;32;28 - 00;30;33;07

Jonathan Hafetz

Right.

00;30;33;08 - 00;30;47;16

Fred Jacob

Exactly. And I think you know it. Joe is like he stands alone in this movie. I mean, he's not just an outsider to the community, which he is. He's really on the outside of the entire dialog of how do you organize or not organize this temple?

00;30;47;18 - 00;31;19;20

Jonathan Hafetz

Well, one way he's being idealistic, but maybe also a little pragmatic comes with respect to the use of scabs. Right? So one thing that the film does a great job highlighting where the company uses scabs, particularly black workers and Italian immigrants. We have that scene in the beginning where there's the violence against the black workers. James Earl Jones, his name is a few clothes, and when they get to town and they get off the train and there's this huge fight scene, and Joe Queenan basically tells the workers, tells the union, you've got to accept everyone.

00;31;19;23 - 00;31;21;11

Jonathan Hafetz

He gives his moving speech.

00;31;21;14 - 00;31;42;20

Movie Dialogue

Union man, my ass. You won't be treated like men. You won't be treated fair. But you ain't man to that coal company. Equipment like a shovel, a gun, the car, a hunk of wood brace. They use you tell you wear out or you break down. Are you buried under a slate? Fall. And then they'll get a new one.

00;31;42;23 - 00;32;00;25

Movie Dialogue

And they don't care what color it is or where it comes from. It doesn't matter how much coal you can load or how long your family has lived on this land. If you stand alone, you just so much shit to those people. You think this man is your enemy. This is a worker in a union keeps this man out.

00;32;00;27 - 00;32;19;07

Movie Dialogue

I ain't a union. It's a god damn club. Now they got you fighting white against color, native against fern, holler against holler. When you know there ain't but two sides of this world. Then that work. And then they don't. You work, they don't. That's all you got to know about the enemy.

00;32;19;09 - 00;32;30;11

Jonathan Hafetz

Basically the idea, like if you want to succeed, you got to be united. So that does seem maybe a little bit pragmatic. What did you make of the use of scabs in the movie? Was that unique to mining?

00;32;30;13 - 00;33;02;03

Fred Jacob

Use of scabs are certainly not unique to mining, but at least from my reading and digging, there was something unique about mining that made it different. When you brought in workers who were Italian born or otherwise foreign born or black workers to do this really, really hard, dangerous job. My understanding from the research I did is that around the time of May 1st, the number of immigrant workers and black workers working in the mines, they outnumbered native white workers at that point.

00;33;02;06 - 00;33;29;00

Fred Jacob

So it was very common part of it because it was such a labor intensive job. You're doing it in these remote geographic areas where there may not be enough people to do this really hard work who are above able and willing to do it. So you had to bring some people in, period. And then on top of it, when you're dealing with labor disputes and employees are on strike and they're withholding their labor, you have the owners believed it was there to keep the mines going and to fight back against the unions.

00;33;29;00 - 00;34;02;24

Fred Jacob

They had to bring in replacement workers. And that's inherently divisive. That's the whole point, I would say, is to divide the pro-union workers from the purportedly possibly anti-union workers, I would imagine. And certainly the movie does a great job of sort of setting this up, as the story we're expected to see is that by bringing in black workers and Italian workers who don't speak English, you know, who are truly foreigners to rural West Virginia, you are creating three groups who will be in opposition to each other.

00;34;03;00 - 00;34;25;15

Fred Jacob

And by creating the groups in opposition to each other, they will fight each other and not the mine owners. That's the whole point. Everything we see, whether it was in Norma Rae. Anytime you read about union work, right, the whole idea is that you are stronger together than you are apart. And to the extent that the owners can keep you apart, it really undermines your power as a unit.

00;34;25;17 - 00;34;41;22

Fred Jacob

It undermines your economic power. It undermines your political power. It undermines your societal power. And so the movie is set up to tell that story in some ways. And I will also confess to you, I think, that I had not seen that one until earlier this year, after you and I talked about it in the last time we did a podcast.

00;34;41;22 - 00;35;20;19

Fred Jacob

So it was a really new and fresh to me. So when I was just watching it, I was convinced the movie we're going to see is really going to be about how all these workers are in opposition to each other and intention with each other. So it took a little bit of a lovely path that really my understanding is true to form with what happened in the mines in West Virginia and probably elsewhere in the early 20th century, that there was such a constant threat of death and danger and accidents and explosions and all the sorts of physical harm, and that we talked about earlier, that the workers were truly bonded together in ways that

00;35;20;19 - 00;35;44;23

Fred Jacob

didn't happen in other industries. There's a historian quoted in the Green Book who said there was like a military type discipline in the mines because any one person could cause an accident that could blow the entire mine up. If you accidentally didn't do a fuze right in your particular little room, and it set off the coal dust and the coal dust caused an explosion or a fire.

00;35;44;25 - 00;36;10;15

Fred Jacob

The fire then could spread and hurt everybody. So there was a a military like bond and discipline across workers. And that I believe, crossed these lines from white workers to Italian speaking workers to black workers. And it made it easier for the unions to organize across racial and cultural and ethnic lines in ways that perhaps other unions weren't able to the mine workers at the time.

00;36;10;15 - 00;36;25;25

Fred Jacob

And this is true of the Wobblies as well. And, you know, one of the things that Joe Carnahan brings to the organizing and made one and the speech that you just played is this idea that, again, we are one big union. All the workers are in it together across the racial lines, like, once you walk into the mine.

00;36;25;25 - 00;36;47;21

Fred Jacob

And that again, great scene with a few clothes where he says, you know, basically people have called me epithets my entire life, but no one's ever called me a scab. And so the mines were amenable to organizing across racial lines. There are a couple like moments, you know, John Sayles, he's such a good filmmaker. I thought it was subtle, but maybe it maybe it's not subtle.

00;36;47;21 - 00;37;04;14

Fred Jacob

I don't know, you told me you think it's subtle, but at the beginning of the movie, there's that scene at the camp where the white workers are playing a fiddle, and then somebody walking, and then they walk over to where the Italians are and they're playing an accordion, and then they walk a little further and they're the black workers are playing a harmonica.

00;37;04;21 - 00;37;19;12

Fred Jacob

And music is important to each of these three different cultures. And then we flash forward, there's a scene later on where everyone's playing together, the same song with the same instruments, and it's just like this great moment. They've made all out of these parts.

00;37;19;14 - 00;37;39;11

Jonathan Hafetz

I agree completely. I mean, I think it's moving. And there's also where over the polenta. Right? The Italian wives of the miners are cooking polenta, which the other miners end up designed to like. Initially the tensions are, you know, not just for the miners and their families, but they bridge the gaps. I think it's really interesting that your point about and the point in the book, it's that something about mining, just the total precariousness.

00;37;39;11 - 00;37;55;16

Jonathan Hafetz

I mean, it's not just we're fighting for higher wages and better conditions and more mean hours, but this is a life threatening nature that, you know, every time you go down in the mine, take your life in your hand. You really got to trust the person. And so it does breed a certain level, I guess, of, you know, kind of cooperation across racial ethnic lines.

00;37;55;19 - 00;38;19;13

Fred Jacob

An Eric Spark, right. The single errant spark could blow your mind. It's also an overlay in the movie from the very beginning of the movie, we know that there was a huge blast and they call it tunnel five. I can't remember exactly how they phrase it. You know what the technical term is? There's a huge classic killed numerous people in the town, from Bertie May's husband to Alma Radner's husband, Mary McDowell character.

00;38;19;20 - 00;38;39;26

Fred Jacob

And it decimated the town who still hanging over the town. And so they knew that they were constantly on the edge of danger when anybody went up to the mine every day. I mean, I can't imagine working a job like that, you know, it's like we are very lucky, even in the mines. We now have fast forwarding, right?

00;38;39;29 - 00;38;59;10

Fred Jacob

We have a huge federal infrastructure that is there to protect mine safety, mine safety and health administration. We have probably not enough, but there are inspectors that go out and inspect the mined. We have probably a very intricate system of mine safety, and I would imagine that mining itself, there have been technological advancements that make it safer as well.

00;38;59;12 - 00;39;23;03

Jonathan Hafetz

Yeah, I remember reading or hearing somewhere, even certain basic things. They used to use a piece of metal. Maybe it was a signaling device and they realized that it could create a spark, and they switched to that material because of all the methane, a gas. And there's another thing they didn't like, which was a way to prevent the accidental explosions from the gas, was something with the way that the light that they use to illuminate the mines are totally pitch black.

00;39;23;03 - 00;39;53;20

Jonathan Hafetz

They created in a way to try to minimize the potential for it to have a spark that would make the whole mine go up. And when we talked a little bit about the law and some of the laws that hinder the miners and labor from organizing conspiracy laws, antitrust laws, enforcement of yellow contracts, trustingly in the film, some of the only or the only representatives of law are the police chief Sid Hatfield, the David Strathairn character, and the Mayor Cable testament, played by Josh Mostel.

00;39;53;23 - 00;40;12;20

Jonathan Hafetz

And these seem to be competing visions of institutional authority and turn out to be the people that stand up for the miners. I think largely because they come from their community, and I know that it Hatfield historically at least, was at worked in the mines when he was younger. How did you see these two characters and how they fit into the story?

00;40;12;23 - 00;40;40;09

Fred Jacob

I think it's fascinating. I think it's fascinating thinking about what was law in Mingo County in 1921, who was law when. It is an accurate portrayal of what happened when the Baldwin Phelps showed up and tried to evict everybody initially, and the mayor and Sid Hatfield show up and say, these warrants are no good, or these eviction notices are no good, you need to go to a judge in the county seat and get real warrant.

00;40;40;12 - 00;41;23;11

Fred Jacob

And at least according to the James Green Book, the Baldwin Phelps were shocked to hear that they had never encountered town officials who were not loyal to the mine owners. So the representation of law is really interesting. And I was struck listening to the commentary to John Sayles commentary, which I know you also listen to. And he said that he always envisioned this movie as a Western, which just made my eyes light up and made me remember being an American Studies major back in the 90s and watching The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, you know, and the whole idea of a Western right is about law and lawlessness, fighting to bring civilization down to a

00;41;23;18 - 00;41;54;00

Fred Jacob

uncivilized part of the country, the western frontier, which was I want to make sure I phrase this right. You know, appropriate now as opposed to man, you know, talking about manifest Destiny, like Westerns are all about how the American culture of the East expanded to the West, taking over parts of this country. And we can certainly talk about all the failures in what we did as a nation in expanding West.

00;41;54;03 - 00;42;20;18

Fred Jacob

But Westerns have a Western movies had an idealistic version of what that was like and what that was about, and it was about the idea of this territory that had never known rule of law being civilized. And that's kind of what this movie is about to write. It just struck me, is we have this lawless community, or areas where there are so many different portrayals of conflicting figures of law.

00;42;20;20 - 00;42;50;18

Fred Jacob

It could be just Mayor Testament who is clearly ineffective as a representative of municipal government. It could be the sheriff who is all courage and bravado as he interacts with the. Baldwin felt it could be the Baldwin Phelps as representative of the true government in Matewan, which is the company. You could write a version of this movie and as celebrated as this historical that was at the time.

00;42;50;20 - 00;43;17;00

Fred Jacob

There were lots of historical accounts that were sympathetic to the company. Like, you could write this from the company's standpoint as the symbol of government. And then there's, of course, Joe Carnahan, who's trying to bring a peaceful view of law that brings the parties together in a true workplace democracy to resolve these issues through peaceful negotiations rather than violence.

00;43;17;03 - 00;43;27;18

Fred Jacob

And so I don't have a good answer for who the government is. You know, who the real government actor is? I think it's it's just fascinating because, like at the end, we don't really know.

00;43;27;20 - 00;43;49;22

Jonathan Hafetz

It's so interesting. And by the way, I think Joe Carnahan is also very surprised at the twist in the movie for him is what he expects the police chief to back the owners. Miner does it. You could see Gary Cooper, Jimmy Stewart playing the David Strathairn character, and he's standing up, you know, against these powerful forces. Baldwin Felts to protect the town.

00;43;49;26 - 00;44;11;10

Jonathan Hafetz

But it's interesting because in the West, the sheriffs that do that are sort of standing up for these kind of law and order principles, protecting the town people in the absence of federal authorities, often in the Westerns. Right. Federal law just can't get there in time. It's ineffectual. Right? Yeah. But here the law writ large is largely on the side.

00;44;11;13 - 00;44;26;10

Jonathan Hafetz

Yeah. I thought was written at the time or is interpret at the time, the 1920s, as you were explaining, is on the side of Baldwin, Felton and the mine owners. So he's something in that sense of a kind of a renegade, but he's standing up for the principle. But it is really interesting to see the through the lens of a Western.

00;44;26;12 - 00;44;45;19

Fred Jacob

Yeah. I mean, it didn't occur to me until John Sayles said it and then it made perfect sense. It's fascinating that, of course, it's Sheriff Hatfield which reigns over Western, and he became a hero for what he did and made one. The UMW made a silent movie called smile and said that was distributed around the country. You know, talking about his exploits.

00;44;45;19 - 00;44;56;24

Fred Jacob

It made one that I think is lost because I tried to find it on the internet and it's not available anymore. But yeah, that kind of standing up to company officials was obviously very unusual at the time.

00;44;56;26 - 00;45;11;17

Jonathan Hafetz

There's that great line where he says, you know, if they had brought more people to, Hartfield tells. And you got ten minutes to leave, you know, your warrant's no good. And the Baldwin Phelps agent says, you know, we brought a bigger force or something. Next time we'll come with guns. And he says, look, I give you five minutes to leave that.

00;45;11;17 - 00;45;27;29

Jonathan Hafetz

Right. So, yeah, you gotta know is, I mean, and the final scene. Right, or something. Fact the final scene does I mean, we talk about a Western. It does feel like it's the final shootout scene. Right? We have final confrontation scene. Baldwin felt guys come bigger, more guns. The town's ready. Yeah, they have people hiding out on the roofs.

00;45;28;06 - 00;45;44;12

Jonathan Hafetz

The second story on Main Street ready to go. And you had the confrontation in Main Street between the mayor's Caitlin Testament. Josh, most character says, no, we're not going to yield. And the shooting starts. I mean, as I understand it, the historical question about who shot first. But that is quintessential Western scene, I think in the movie.

00;45;44;15 - 00;45;52;13

Fred Jacob

Yeah, you're right. I mean, it's totally, you know, high Noon, right? The meeting on the main drag of town, which of course was the railroad for the big shootout at the end.

00;45;52;16 - 00;46;22;11

Jonathan Hafetz

And so Joe kind of ham. Yeah. Spoiler is killed in the fighting, but Sid Hatfield is heroic in the fight and lives to fight another day. Although, you know, maybe we'll talk about what happens after made one right after the battle of May 1st because, as the film notes towards the very end, this is maybe just the opening or one of the opening battles in the larger Great Coalfield War, the continuing labor violence after the battle of May 1st and Sid Hatfield, who is prosecuted for the violence that may want engaged in.

00;46;22;17 - 00;46;37;08

Jonathan Hafetz

He's acquitted. He's forced to stand trial for something else and a different county district. And when he's on the courthouse steps, I think it's see, Lily, who's masquerading as a union member, but he's in cahoots with the company, shoots him in the head, executes it. Right?

00;46;37;10 - 00;47;12;02

Fred Jacob

Yes. I mean, Maitland was sort of the spark of the second coal mine was and ultimately led to the Battle of Blair Mountain, which was one of the most. What's the right adjective? I was about to say horrific, shocking, all the adjectives, surprising, horrible events that affected organized labor and probably that ever happened on US territory involving tens of thousands of miners who basically engaged in a battle on US territory with coal miners, with the Baldwin felt and representative of mine owners.

00;47;12;04 - 00;47;55;24

Fred Jacob

When Hatfield was murdered by the Baldwin Phelps on the steps of the courtyard, it sparked this huge coal mine war, part of what had happened was on the anniversary of the mine massacre, which happened a couple of months before Hatfield was murdered. The governor of West Virginia declared martial law because strike activity had been so prevalent and so violent that the governor, who the UMW had thought they might be able to work with, declared martial law and turned over the state to the Adjutant General of the West Virginia National Guard, who was given the power to arrest any troublemaker at will and hold them without charges for as long as he would like to do

00;47;55;24 - 00;48;21;29

Fred Jacob

so. So, not surprisingly, in the wake of this, dozens and dozens of strikers were put in jail, particularly in Mingo County, without charges, based on allegations that they were involved in some sort of troublemaking, most likely because they were strikers, most likely because some of them were black, most likely because some of them were not native. Not born in the United States.

00;48;22;01 - 00;48;43;01

Fred Jacob

And at the same time, this is right after World War One. The country had seen a spike in unemployment. So workers had been laid off at the mines. They were seeking better wages. They were seeking better protections. So there were economic reasons for the strike. There were political reasons for the strike. There were reasons for this huge strike there.

00;48;43;03 - 00;49;07;17

Fred Jacob

And essentially because there were no legal avenues for employees and workers to exercise their right, there were no political avenues there shut down by the governor of the state, who declared martial law. There were fewer economic avenues because it was after World War One. And we are in the midst of this depression and for all the reasons we talked about, perhaps there was sort of a culture of West Virginia where people took matters into their own hands.

00;49;07;20 - 00;49;34;03

Fred Jacob

The miners throughout the state began to march towards Mingo County and towards meet one with the intent of freeing the workers who had been unjustly held in jail. And over the course of August and September 1921, 15,000 miners, all wearing red bandanas around their neck, which led to the term rednecks, which I don't know if you notice, got a shout out at the Democratic National Convention.

00;49;34;03 - 00;49;56;25

Fred Jacob

One of the speakers there talked about the march on Blair Mountain and the origin of the term redneck. And this marching force just march towards Mingo County. And all of them were armed. Many of them were former World War One soldiers who marched in their uniforms. And the governor refused to do anything. And because of this, it escalated and escalated.

00;49;56;28 - 00;50;27;01

Fred Jacob

And by the time they were pitched at Blair Mountain. And if you read the history of this, I don't read a lot of war histories, but that's what it reads like. It reads like we are talking about positions, these different divisions commanders, you know, and it reads like a war because it was there were volleys of ammunition and gunfire that were shot back and forth between the Baldwin Felts and other guards who were hired by the mine owners and the mine workers.

00;50;27;05 - 00;51;07;21

Fred Jacob

And it all culminated in essentially, the mine owners hiring planes to drop bombs on American workers in the mountains of West Virginia. They dropped gas bombs and they dropped munition bombs that killed dozens of workers. And at that point, things had reached such a fever pitch that President Harding finally intervened, and he allowed federal troops, 2100 federal troops to enter West Virginia to bring down the tensions and to try to end this battle, which they did successfully, because the miners, again, many of them were World War One veterans.

00;51;07;24 - 00;51;34;27

Fred Jacob

They would not take up arms against the US Army, and they viewed it as a victory. When the Army finally came in to bring down these tensions and resolve this conflict. It's horrible. Things often are in modern times and is divisive, as our society sometimes feels. We have yet to see 15,000 Americans march on a county government with arms bombed by their citizens.

00;51;34;29 - 00;51;38;15

Fred Jacob

So it was a dark time, a really dark time for our country.

00;51;38;17 - 00;51;48;00

Jonathan Hafetz

I think it's really important that you paint a picture to give an idea of what the stakes were and what the level of violence was. I mean, I the largest insurrection after the Civil War, armed insurrection.

00;51;48;02 - 00;51;50;19

Fred Jacob

It's unthinkable. I don't think about.

00;51;50;21 - 00;52;16;10

Jonathan Hafetz

And especially to you in terms of when we think about what happens after. Right. So what does happen after the Coalfield War, the Battle of Blair Mountain we talked about on the prior episode, Norma Rae. Right. You talked to 1970s hard fought battle to try to organize textile workers in the South, and there was still some of the violence, some of the threats, but does seem very different in terms of the dynamics that were involved and the steps that the company would go.

00;52;16;13 - 00;52;21;11

Jonathan Hafetz

So what happens after May 1st, after the Coalfield War, both in mining and in generally.

00;52;21;14 - 00;52;44;22

Fred Jacob

Eventually by the New Deal, the National Labor Relations Act was passed and the point of the National Labor Relations Act is to funnel violence and conflict and even strike activity, to legal process and to reserve strikes for economic warfare, not for what we would call recognition of warfare, which essentially unions had to strike to get recognition in the first place.

00;52;44;24 - 00;53;22;00

Fred Jacob

Stepping back sort of the 1920s, I think we're really tough time for the mine workers, even though the economy was roaring, at least according to what I've read, there was still a lot of intransigence by the mine owners. But once the depression hit and the economy truly just fell into the depths of the darkest economic depression this country had ever seen, there were a number of laws that Congress passed that really allowed the mine workers to finally organize in West Virginia, and probably also in eastern Kentucky and throughout Appalachia, a lot of the places that they had struggled previously.

00;53;22;00 - 00;53;55;17

Fred Jacob

So Congress, as I mentioned earlier, passed the North LaGuardia act, which prohibited federal courtroom enjoining labor activity. And also, for the first time in a federal law, a firm that employees had a right to organize unions and to band together to improve their working conditions. When Franklin Roosevelt was elected president, one of the very first things he did in his famous 100 days was pass the National Industrial Recovery Act and part of the National Industrial Recovery Act, explicitly protected employees rights to join a union.

00;53;55;20 - 00;54;29;18

Fred Jacob

Section seven A and it use that language that the very same letter. But we enforce as part of the National Labor Relations Act now and under the National Industrial Recovery Act, and then under the National Labor Relations Act, which was passed in 1935, the mine Workers were very successful in organizing, as I mentioned, all of these holdouts. And, you know, part of it was that a lot of employers went to dark space and were willing to try anything during the depression and maybe just kind of threw their hands up and said, let's give this a shot.

00;54;29;21 - 00;54;57;18

Fred Jacob

A big part of it was that federal law for the first time, explicitly said it is the policy of the United States to support collective bargaining. That's in the first section of the National Labor Relations Act. And during this time of optimism, as the country was emerging from the depression, organizing throughout industries not just coal, but all sorts of industries exploded.

00;54;57;18 - 00;55;20;13

Fred Jacob

And there was work that unions had to do that sometimes got violent. I mean, we can't forget sit down strikes for the UAW, the auto workers, and where they took over a number of factories in Flint, Michigan, and other instances like that where they did use a certain amount of violent force. But it was nothing like what we saw in West Virginia.

00;55;20;16 - 00;55;32;22

Fred Jacob

And the UMW was really able to, I think, quarter to market on mines in this country. Their density grew exponentially along with the density in other industries.

00;55;32;24 - 00;55;52;21

Jonathan Hafetz

Yeah, I think that does kind of help to the differences between Palmer and other iconic movie about the labor movement, and made one kind of have the jokey character there. The Bromley character comes in right from the outside, trying to organize the textile workers. One thing that jumps out is, you know, when there's violence or when the textile workers do something bad, right?

00;55;52;28 - 00;55;57;07

Jonathan Hafetz

It's not, what are we going to do? Or how are we going to strike? This is great. We can go to court.

00;55;57;10 - 00;56;20;18

Fred Jacob

Yes, yes. Right. And we talked about in the podcast how much the law was this off screen character that so much of what's going on in Norma Rae is because there was a legal process that supported union organizing and that legal process really based on the National Labor Relations Act, and that you had workers at the I mean, I'm assuming I always want to see the NLRB version of Norma Rae, right.

00;56;20;18 - 00;56;48;19

Fred Jacob

Of all the NLRB workers litigating cases, but you had folks who were making sure that the company had their feet held to the fire. And the company of Norma Rae in real life, JP Stephens, the were among the worst of the offenders. And even there, what they did to fight the union was just sort of an all out refusal to obey any board or court order as long as they could possibly hold out.

00;56;48;21 - 00;56;59;18

Fred Jacob

They were not dropping bombs on the textile workers that were trying to organize. You know, it was funneled through a legal process, and there was legal remedy that eventually came to make the union happen.

00;56;59;20 - 00;57;24;18

Jonathan Hafetz

Let's bring one other movie in the documentary, I Look at you before Barbara Koppel's award winning 1976 documentary Harlan County, USA, so roughly contemporaneous with Norma Rae, which depicts a miners strike in 1970, in eastern Kentucky. And it does raise some similar issues use of scabs, economic power, and the machinery of law to resist unions. But we also see violence, too.

00;57;24;18 - 00;57;34;09

Jonathan Hafetz

So what is Harlan County, USA, which predates May 1st and production, but follows it and the events depicted help fill in John Sayles as story it made one.

00;57;34;11 - 00;58;03;16

Fred Jacob

When I watched Meet One, I was struck by sort of the funny, the interesting chronological context of it. How, as you said, Harlan County was filmed before May 1st, but takes place after May 1st. And so to the extent of how much does this influence how much is Matewan in some ways an allegory about Harlan County. I always love to paint an optimistic, Pollyanna ish picture of labor, but I recognize that these battles are hard and these battles are real.

00;58;03;18 - 00;58;26;13

Fred Jacob

And there's a lot at stake. And so even in Harlan County, where the union is incumbent and the union is recognized, and what's going on is extreme hard bargaining for a new contract, if I remember correctly. So that's the court issue. And employees go on strike. They certainly talk about how dangerous it is and how hard it is to work in the mines.

00;58;26;13 - 00;58;51;02

Fred Jacob

And if I remember correctly, there are some older miners who talk about the old days, like referring back to almost the May 1st days, but it's not about people dying in the mines every day. It really goes to these hard economic issues. And again, like unions have a limited toolbox of tools that they use in negotiating. Strikes are the most important tool that they have.

00;58;51;04 - 00;59;13;23

Fred Jacob

And what we see in Harlan County is this really powerful depiction of what happens when a community goes on strike. And so if you see like one of the things we see over and over again, as you said, Jonathan, is the workers trying to prevent, in 1970, the cars from driving in to the mine containing all the scabs, you know, can they block the road?

00;59;13;23 - 00;59;42;17

Fred Jacob

Can they not block the road? And it's reminiscent of and it's not quite the violence, but, you know, it's reminiscent of how the strikers in West Virginia in the 1920s felt they needed to use every tool at their disposal to have stopped people from taking over their jobs. Right, because that's their most powerful weapon. It's interesting. Like, how does it fill out the story in a post, like looking at it retrospectively, like using Harlan County as a tool to think about, all right, what happened?

00;59;42;21 - 01;00;07;12

Fred Jacob

Now that one is organized, theoretically, this is how the NRA and labor law, American labor law, is supposed to work. We're supposed to have parties recognize each other, employees be able to choose a union, and then sometimes when they're negotiating a contract, it's really, really hard bargaining and the law, for good or for bad, still allows employers to bring in replacement workers.

01;00;07;12 - 01;00;36;06

Fred Jacob

And that's been controversial since the Supreme Court upheld that practice shortly after the NRA was passed in the late 1930s. There have been many legislative attempts to prohibit that practice, but it's still legal. So you're seeing economic warfare at play in Harlan County, and that's again, how it's supposed to work. And Harlan County is just a gut wrenching portrayal of how it really both can inspire a community to fight and how it hurts the community.

01;00;36;08 - 01;00;59;17

Fred Jacob

And as you said, the sad part is that ultimately, what brought the parties to the table was the murder of a young man with a wife and family. And I don't think that murder was ever solved. We ever knew who really did it. But that's what brought the parties to the table. So, you know, the presence of violence is still, I guess, still there in Harlan County and still heartbreaking to say.

01;00;59;20 - 01;01;13;28

Jonathan Hafetz

That it was important, I think, as the union saw it in Harlan County, to get the national spotlight on to publicizing that and all of that together, to help bring them to the table. But, you know, there's some great lines from some of the people who were involved on behalf of the union for saying, you know, the concessions.

01;01;14;05 - 01;01;18;16

Jonathan Hafetz

That's just for today. You know, it doesn't end. It's an ongoing struggle.

01;01;18;18 - 01;01;30;10

Movie Dialogue

Once a concession is won and once a strike is won, that the workers have to move right on to the next struggle and they don't. The concession that was won, we're going to lose it.

01;01;30;12 - 01;01;49;22

Jonathan Hafetz

But also what you said, the strike and the power of the strike being the most important thing. And ultimately it's the law to protect that. Right. But at the end of the day, it's really about organizing the labor power. There's a great line where they talk about injunctions. What they say is you need the lawyers not to get the injunction.

01;01;49;26 - 01;02;00;17

Jonathan Hafetz

So few people can go demonstrate. You need the lawyers after you go out and you strike and show force and the management response to help get you out of trouble.

01;02;00;20 - 01;02;18;10

Movie Dialogue

I don't think you'll never win a strike by having six people on the picket line. I there's no way, I mean, that you can win a strike with six picket. So you got violated injunctions, and the lawyers are mine to get you out of trouble after you get in, not to get you out of trouble before you get in.

01;02;18;12 - 01;02;26;04

Jonathan Hafetz

But still, ultimately, people demonstrating people collectively exercising their power. That's the critical factor.

01;02;26;07 - 01;02;47;11

Fred Jacob

Yeah, exactly. And it's interesting, as a labor lawyer, not a labor economist or a labor historian, you know, occasionally I wade into that world. Right? And you talk to labor economists in particular. We think about success in the labor world as a labor lawyer and working at the National Labor Relations Board. In my other life, you know, my real life, you know, it's like, how many elections are we running?

01;02;47;11 - 01;03;13;08

Fred Jacob

You know, how many certifications have there been? What are the result of those certifications? How many people do we get back to work after they were fired? How many people did we hear? How many times did we get parties to get back to the bargaining table and keep negotiating? Right. But labor economists and labor historians, they will look at strike activity is an increase probably the most important factor in figuring out union power because like that is the most important weapon.

01;03;13;08 - 01;03;32;01

Fred Jacob

And so if you look at how strike activity, you look at strike activity over time. It peaked probably in the 60s and 70s and has been on a steady decline in terms of the number of major strikes. It's something that Bureau of Labor Statistics tracks. And then Cornell, the Cornell School of Industrial Labor Relations, just recently put out.

01;03;32;09 - 01;03;54;22

Fred Jacob

They started tracking it, too. So it started to decline. But then it's picked up again, and we saw a lot of really, really prominent strike activity with the UAW strikes and the SAG after strike and the Writers Guild strikes and and Sean Fein is suggesting there should be a general strike in 2028 when the agreements are up at the three big carmakers.

01;03;54;22 - 01;04;25;22

Fred Jacob

So we may be entering a world where there's more strike activity, and it will be interesting to see if the changed economy and the changed nature of the businesses that are being organized now allow that to happen more. One of the reasons I think we saw a dip in strike activity, right, is that so much of the traditional manufacturing sectors had outsourced their work to other countries, or from northern states to less unionized southern states, so that it was easier to get replacement work and the power of the strike diminished.

01;04;25;25 - 01;04;40;02

Fred Jacob

We're seeing a lot more organizing and more service sectors and different sectors now. And so whether the strike becomes a more powerful weapon again, it will be interesting to see what what all those labor economists and historians say in a couple of years.

01;04;40;04 - 01;04;52;10

Jonathan Hafetz

Super interesting and also reasons now to kind of go back and watch made one made right when striking and the power of labor was declining and a low level to now when it's much stronger, it's kind of a different world.

01;04;52;12 - 01;05;12;16

Fred Jacob

Then, you know, again, the National Labor Relations Act gets a lot of criticism, and I won't comment on what's justified and what's not justified. But, you know, there are lots of opinions out there and they're easy to find. But it does protect the right to strike. And you can't fire someone for striking, and you do have to bring them back to work if you have openings and so that is a lot different.

01;05;12;21 - 01;05;36;08

Fred Jacob

And it is illegal under the National Labor Relations Act to require employees to sign a yellow dog contract. It's illegal under the North LaGuardia act to randomly enjoin a labor activity. So a lot of the firm we saw in May 1st has been remedied legally. And so we're dealing with more discrete and more narrow issues that I think focus on the party's economic power.

01;05;36;10 - 01;05;43;16

Jonathan Hafetz

Well, Fred, it's been so great to have you on again. It's a pleasure talking you about May 1st and labor law in the labor movement. So thanks so much.

01;05;43;19 - 01;05;45;27

Fred Jacob

Thank you so much. I was great coming back.

Further Reading

Green, James, The Devil Is Here in These Hills:West Virginia's Coal Miners and Their Battle for Freedom (2015)

Hood, Abby Lee, “What Made the Battle of Blair Mountain the Largest Labor Uprising in American History,” Smithsonian Magazine (Aug. 25, 2001)

Moore, Roger, “A Masterpiece that reminds us why there is a Labor Day,” Movie Nation (Sept. 2, 2024)

Sayles, John, Thinking in Pictures: The Making of the Movie Matewan (1987)

Fred B. Jacob is the Solicitor of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). As Solicitor, Mr. Jacob serves as the chief legal adviser and consultant to the entire Board on all questions of law regarding the Board’s general operations and on major questions of law and policy concerning the adjudication of NLRB cases in the Courts of Appeals and the U.S. Supreme Court. The Solicitor also acts as the Board’s legal representative and liaison to the General Counsel and other offices of the Board. From 1997 to 2014, Mr. Jacob worked as an attorney, supervisor, and Deputy Assistant General Counsel in the NLRB’s Appellate and Supreme Court Litigation Branch. Before joining management, he served as Grievance Chair of the NLRB Professional Association, the union representing Washington, DC-based NLRB attorneys. Mr. Jacob is Professorial Lecturer in Law at the George Washington University School of Law. Mr. Jacob has previously taught labor and employment law courses at Georgetown University Law Center and the College of William and Mary School of Law