Episode 27: Absence of Malice (1981)

Guest: Brian Hauss

Listen Anywhere You Stream

~

Listen Anywhere You Stream ~

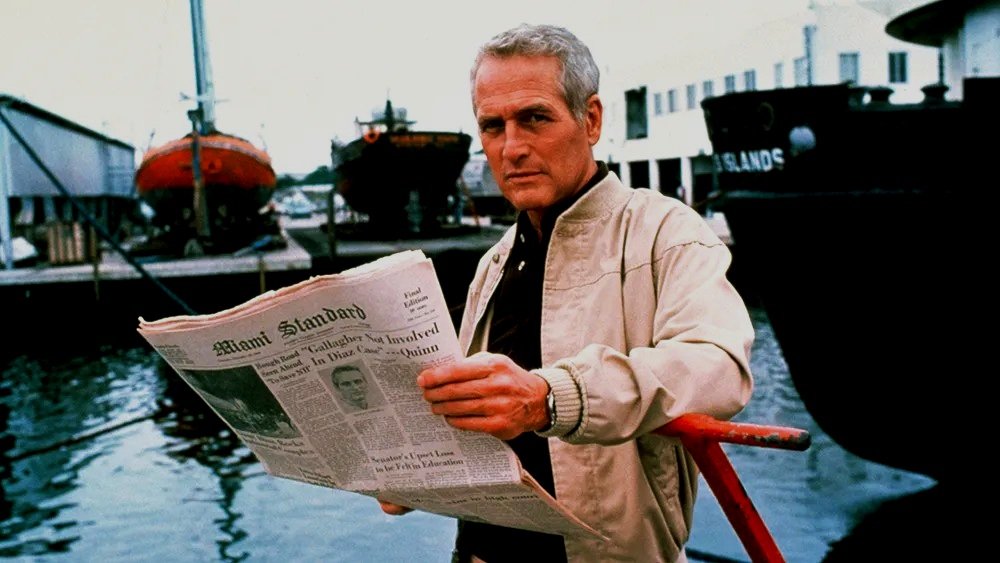

This episode examines Absence of Malice, a 1981 drama directed by Sidney Pollack. After Miami-based newspaper reporter Megan Carter (Sally Field) is tipped off by Justice Department organized crime strike force chief Elliot Rosen (Bob Balaban) about a criminal investigation into the disappearance and likely murder of a local union official, her paper runs a sensational front-page story. But the supposed target of the investigation, Michael Gallagher (Paul Newman), the son of an infamous bootlegger, is innocent; Rosen, the strike force chief, has leaked his name to the press to try to squeeze Gallagher for information. Gallagher is incensed and tries to pressure Megan to reveal her source. Megan initially refuses but later relents after her story unexpectedly leads to the tragic death of a friend of Gallagher's. Gallagher and Megan also become romantically involved. Gallagher hatches a plot to get even and get the government off his back. He causes an unsuspecting Megan to write another sensational story, this time implicating the District Attorney in a bribery scheme that Gallagher has invented. When the truth is revealed, both the prosecutors and the newspaper are humiliated, the victims of their own game of leaking information and reporting about it. Absence of Malice provides an insightful, if unflattering, picture of how newspapers operate and some of the ethical and moral complications that can result from the robust protections afforded the press under the First Amendment. I’m joined by Brian Hauss, a senior staff attorney with the ACLU Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project, who has litigated numerous landmark First Amendment cases.

Brian Hauss is a senior staff attorney with the ACLU Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project. Since joining the ACLU in 2012, he has litigated cases defending the First Amendment rights of writers, journalists, media organizations, activists, advocacy groups, labor unions and private citizens. He has authored or co-authored numerous Supreme Court amicus curiae briefs on behalf of the ACLU and other groups. He also regularly discusses First Amendment issues in the media and at law schools throughout the country. Brian was previously a staff attorney with the ACLU Center for Liberty, where he focused on combating religious refusals to comply with anti-discrimination laws. He also spent two years as the ACLU’s William J. Brennan First Amendment Fellow. Brian is a graduate of Yale University and Harvard Law School. He served as a law clerk to the Hon. Marsha S. Berzon of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

30:20 A troubling increase in leak prosecutions

32:31 The “Leaky Leviathan”: How the government uses leaks

39:06 The obligations of the press

42:43 The legal vs. ethical obligations of the press

48:11 Assessing critiques of the absence of malice standard

54:59 Timeless questions explored by the film

0:00 Introduction

3:31 The meaning of “absence of malice”

8:15 Deciding what a paper can print

11:22 A skeptical take on the absence of malice standard

15:02 The meaning of “public figure”

20:47 A newspaper reporter’s First Amendment privilege?

26:10 How the government handles leaks

Timestamps

-

00;00;14;13 - 00;00;35;23

Jonathan Hafetz

Hi, I'm Jonathan Hafetz, and welcome to Law on Film, a podcast that explores the rich connections between law and film. Law is critical to many films. Film, in turn, tells us a lot about the law. In each episode, we'll examine a film that's noteworthy from a legal perspective. What legal issues does the film explore? What does it get right about the law and what does it get wrong?

00;00;35;26 - 00;01;07;16

Jonathan Hafetz

How is law important to understanding the film? And what does the film teach us about the law and about the larger social and cultural context in which it operates? This episode, we'll look at Absence of Malice, a 1981 drama directed by Sydney Pollack. After Miami based newspaper reporter Megan Carter, led by Sally field, is tipped off by Justice Department organized crime strike force chief Elliot Rosen, played by Bob Balaban, about a criminal investigation into the disappearance and likely murder of a local union official.

00;01;07;19 - 00;01;29;24

Jonathan Hafetz

Her paper runs a sensational front page story, but the supposed target of the investigation, John Michael Gallagher, played by Paul Newman, is the son of an infamous bootlegger is nonetheless clearly innocent. Rosen, the strike force chief, has leaked Gallagher's name to the press to try to squeeze Gallagher for information. Gallagher is incensed and tries to pressure Meghan to reveal her source.

00;01;29;25 - 00;01;51;27

Jonathan Hafetz

Megan initially refuses, but later relents after her story unexpectedly leads to the tragic death of a friend of Gallagher. Gallagher and Megan also become romantically involved. Gallagher then hatches a plot to get even and get the government off his back. He causes an unsuspecting Megan oh, he's out for a scoop to write another sensational story, this time implicating the district attorney in a bribery scheme.

00;01;52;03 - 00;02;12;25

Jonathan Hafetz

Gallagher is invented when the truth is revealed. Both the prosecutors and newspaper are humiliated, the victims of their own game of leaking information and reporting about it. Absence of malice provides an insightful, if unflattering, picture of how newspapers operate, and some of the ethical and moral complications that can result from robust protections afforded the press under the First Amendment to the Constitution.

00;02;12;27 - 00;02;39;08

Jonathan Hafetz

Joining me to talk about the film is Brian House. Brian is a senior staff attorney with the ACLU speech, privacy and Technology Project at the ACLU. Brian has litigated numerous landmark First Amendment cases. Some of the cases he's litigated include Rodriguez Cotto versus Lucia Uriarte, First Amendment challenge to Puerto Rico's false alarm statute card versus Mag Ileana, First Amendment challenge to New York's courthouse protest statute.

00;02;39;15 - 00;03;05;10

Jonathan Hafetz

Zephyrs ACLU, where Brian represented the ACLU in a defamation suit against it. Converse bar, where Brian was counsel, and Michael Cohen's challenge to his re confinement in retaliation for his plans to write a book critical of then-President Donald Trump. Turtle Island Foods for. A First Amendment challenge to Arkansas's food labeling statute, which prohibited terms like veggie burger and Jordan Brand events.

00;03;05;11 - 00;03;26;07

Jonathan Hafetz

A First Amendment challenge to an Arizona law restricting boycotts of Israel. Brian is a graduate of Yale University and Harvard Law School. He served as a law clerk to the Honorable Marcia Esposito of the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. And I should add, Brian is a former colleague of mine from the ACLU and a frequent dining partner around New York City.

00;03;26;11 - 00;03;28;15

Jonathan Hafetz

Brian, it's great to have you on the podcast.

00;03;28;18 - 00;03;31;00

Brian Hauss

Thanks so much, John. It's a real pleasure to be here.

00;03;31;02 - 00;03;37;25

Jonathan Hafetz

So let's start with the title Absence of Malice. What does it mean from a legal perspective and what role does it play in the film?

00;03;37;27 - 00;04;07;26

Brian Hauss

The phrase absence of malice goes to one of the most important terms in First Amendment law or constitutional law generally, which is the actual malice standard that the Supreme Court established in New York Times versus Sullivan. And that was a case where essentially a sheriff, I believe, in Alabama, sued the New York Times for defamation because the times had run an advertisement that accused his department of engaging in various forms of misconduct in policing a civil rights protest in Alabama.

00;04;08;00 - 00;04;33;07

Brian Hauss

And he said that there were numerous factual inaccuracies in the advertisement. It was trying to hold the times liable for defamation and won a substantial judgment in the Alabama courts. The Supreme Court reversed the decision, and what it said is it went all the way back to the Sedition Act controversy, which is when the federal government tried to pass laws 1798, making it a crime to share libelous statements about the United States government to publish libelous statements.

00;04;33;07 - 00;04;59;04

Brian Hauss

And the federal administration used that to prosecute dissenters in the Democratic Republican Party. And this record looked at that history and said, you know, the Sedition Act was repealed when Jefferson came into office. And that reflected an emerging national consensus that we don't prosecute falsehood and that, you know, in order for our democracy to exist, the court in particular, relied on James Madison's opposition statements opposing the Sedition Act.

00;04;59;08 - 00;05;20;14

Brian Hauss

Madison basically hypothesized that in order to have a free and democratic republic, you need to have robust public debate about people seeking public office about their qualifications for office, about their misconduct in office, and that the threat of prosecuting people for engaging in that debate, you know, even on grounds of falsehood, threatened the whole basis of democratic government.

00;05;20;16 - 00;05;43;19

Brian Hauss

And Supreme Court said, you know, that's true when it comes to prosecutions, but it's also true when it comes to ruinous libel judgments. The court there was really looking at the way in which a lot of segregationist administrations in the South at that time, in the Jim Crow South, were using and abusing defamation law to prevent northern newspapers from coming into the South and investigating all the abuses that were going on.

00;05;43;23 - 00;06;05;29

Brian Hauss

And the court said, no, that presents just as much of a threat as the old sedition prosecutions. And so the same principle that requires us to say that when you want democratic debate to be uninhibited, robust and wide open, to use Justice Brennan's phrase, we need to provide breathing room. And so, even though, you know, speech that defames somebody that injures the reputation, even when it's false, it's not necessarily protected by the First Amendment.

00;06;06;05 - 00;06;24;16

Brian Hauss

We still impose some additional safeguards to ensure that people can engage in speech that they believe to be true without worry, that being worried that they're going to be hauled in front of a partial or biased earlier judge, or that, you know, minor inaccuracies are going to prevent them from being able to do their jobs and inform the public about what's going on.

00;06;24;16 - 00;06;46;07

Brian Hauss

And so the Supreme Court said, I'm just going to quote it here. The constitutional guarantees require, we think, a federal rule that prohibits a public official from recovering damages for a defamatory falsehood relating to his official conduct, unless he proves that the statement was made with actual malice. That is, with knowledge that it was false, or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.

00;06;46;10 - 00;07;16;25

Brian Hauss

And just to add one little additional detail there, the court later clarified in the case of obscene amount versus Thompson, when they say reckless disregard, what they really mean is strong, subjective doubts about the likelihood that the statement that's being published is true. So it's not recklessness. And I think in the way a lot of lawyers might think of recklessness, but it really is a sort of special constitutional version of recklessness that requires the publisher to genuinely believe or not care whether what they're saying is true, as opposed to just sort of being foolhardy.

00;07;16;27 - 00;07;32;28

Brian Hauss

So that's where the phrase actual malice comes from. And it's, you know, New York Times versus Sullivan. And I think one of the most important decisions to come out of the Supreme Court, and it's what's enabled this very robust culture of news reporting that we have in the United States.

00;07;33;00 - 00;07;55;00

Jonathan Hafetz

Picking up on some really lofty principles here. Right. We're talking about ensuring robust Democratic debate. And then in the context of New York Times, we're Sullivan protecting racial minorities. The movie released in 1981. So we're 15 plus years after New York Times. For Sullivan, there's a number of ensuing events, but the events in the movie are not quite so lofty.

00;07;55;01 - 00;08;16;12

Jonathan Hafetz

Right? We have the government leaking information, a government prosecutor or strikeforce chief, Elliot Rosen leaking information about someone, Scott Gallagher to the press, that the press will run the story and pressure Gallagher to come in and cooperate. There's a scene, first of all, with Meg, played by Sally field and her editor, discussing how they can write the story.

00;08;16;15 - 00;08;20;07

Elliot Rosen

Under Investigation Week and we say is the suspect.

00;08;20;07 - 00;08;21;25

Megan Carter

I still don't know what he suspected us.

00;08;21;26 - 00;08;28;24

Elliot Rosen

Suspected in the murder of Joey. Do I have to say murder is no better presumed murder. Then you're missing six months. You're dead. Okay.

00;08;28;28 - 00;08;32;12

Megan Carter

Prime suspect, I don't know. He's prime. Maybe they have somebody.

00;08;32;12 - 00;08;46;19

Unknown

Prima key. The key. He writes. You want anybody to read this? You keep watering it down. Informed sources. Well informed Nick. If he wanted to.

00;08;46;19 - 00;08;48;13

Megan Carter

Leak the story, why didn't he just tell me off.

00;08;48;13 - 00;08;57;22

Elliot Rosen

The record instead of talking out of school? He's got you snooping through government files. Smart guy. Sources in the federal building. It sounds like the janitor who?

00;08;57;25 - 00;09;03;10

Megan Carter

Knowledgeable sources. Knowledgeable. So why did Rosen want it out?

00;09;03;12 - 00;09;12;26

Elliot Rosen

Maybe he's trying to be a nice guy. Maybe he wants us to owe him a favor. Maybe he likes your leg. We try to figure out why people leak. Stories were published monthly. David. Jack better read this.

00;09;12;28 - 00;09;32;12

Jonathan Hafetz

He's going to love it. And then after they've talked about this, Meg and the editor go talk to the paper's attorney. And they have this very informative discussion about what, if any, limits there are on the paper's ability to print the story in light of the robust First Amendment protections.

00;09;32;14 - 00;09;40;12

Elliot Rosen

Now then, madam, you proposed to say that Mr. Michael Colin Gallagher is the proximate cause of the demise of the esteemed Mr. Diaz.

00;09;40;16 - 00;09;43;17

Megan Carter

That's not what it says. It says he is under investigation.

00;09;43;20 - 00;09;55;14

Elliot Rosen

But Mr. Gallagher will think we make him out a murderer, as will his friends. Neighbors. Let us assume that he is neither a murderer. Another subject of investigation for same. Let us suppose that your story proves to be false. On its face.

00;09;55;21 - 00;09;56;21

Megan Carter

The story's true.

00;09;56;26 - 00;10;02;10

Elliot Rosen

That of newspapers printed nothing but truth. They need never employ attorneys, and I should be out of work, which I am not.

00;10;02;16 - 00;10;03;24

Megan Carter

I read the file.

00;10;03;26 - 00;10;19;15

Elliot Rosen

I'm not a whit interested in the facts. I'm concerned with the law. And the question is not whether your story is true. The question is, what protection do we have if it proves to be false? Now, then, Mr. Gallagher is not a public official, nor is he likely to become one. Okay. Is he a public figure?

00;10;19;18 - 00;10;24;00

Megan Carter

He's not going to sue, for God's sake. So what does it take to make him a public figure?

00;10;24;02 - 00;10;36;08

Elliot Rosen

If I knew that I should be a judge, then never tell until it's too late. I must admit, I'd be more comfortable if he were a movie star or a football coach. Football coaches are very safe indeed. Have we spoken with Mr. Gallagher?

00;10;36;10 - 00;10;38;11

Megan Carter

We don't exactly call the Mafia for comment.

00;10;38;18 - 00;10;52;26

Elliot Rosen

Please make the attempt. If he talks to us, we'll include his denials, which will create the appearance of fairness. If he declines to speak, we can hardly be responsible for errors, which he refuses to correct. And if we fail to reach him, at least we try.

00;10;53;02 - 00;10;54;10

Megan Carter

What are you telling me, counselor?

00;10;54;15 - 00;11;11;27

Elliot Rosen

I'm telling you, madam, that as a matter of law, the truth of your story is irrelevant. We have no knowledge. The story is false. Therefore we're absent. Now us. We've been both reasonable and prudent. Therefore we're not negligent. We may say whatever we like about Mr. Gallagher, and he is powerless to do us harm. Democracy is served.

00;11;11;29 - 00;11;16;19

Jonathan Hafetz

So what was your impression of the scene between Meg, the editor, and the paper's lawyer?

00;11;16;22 - 00;11;36;03

Brian Hauss

So I think these scenes really go to the heart of this movie and why I love this movie so much, because this movie is the skeptics take on actual malice and what it enables and what it encourages. And I think it's important. And although I'm a true believer in New York Times versus all of them, I think it's important to wrestle with the skeptics take.

00;11;36;04 - 00;11;57;04

Brian Hauss

And I think this is a brilliant version of that. And I think the conversations that Meg has first with Mac, her editor, and then with David Lawyer really illustrate the sort of pitfalls that can happen when newspapers focus so much on the legal standard, as opposed to the ethical standard to first, you know, you have that conversation with Meg and Mac, the editor.

00;11;57;06 - 00;12;16;08

Brian Hauss

Meg has gotten this tip from Roseanne who's like portrayed, I think, brilliantly by Bob Balaban, one of my all time favorite band performances. And like, you know, he's expertly engineered for her to receive this information. She knows from the beginning, you know, she's not a naive reporter. She understands exactly what's going on, that he's providing this thing to her, and she picks it up immediately and runs with it.

00;12;16;12 - 00;12;35;01

Brian Hauss

And she's in the editing room with Mac, and she's talking about it, and she's actually wondering to herself is like, why would he give me that? What's going on here? He's starting to think to the next step of what's this all for? And Mac basically says, you know, if we question every time someone gave us a leak why they did it, what their motive was, you know, we would publish monthly, which is a great little one line.

00;12;35;07 - 00;12;53;19

Brian Hauss

But his point is like, don't worry too much about it. Don't think too much about it. That's not important. The important thing is we have this information, it's newsworthy, and we're going to publish it. And you can even see them as they're typing it up. Right? He's taking her language and making it more incendiary, suggesting more strongly that Gallagher is under investigation, even stronger than what she read in the files.

00;12;53;19 - 00;13;08;13

Brian Hauss

And he justifies this to her by saying, why do you want people to read it or not? Right. So first you have that in a conversation with the editor where he's just completely unconcerned about why this is happening, what the deeper truth is, they've got the incendiary information, and so they're just going to go publish it. And that's the business end of the news.

00;13;08;15 - 00;13;23;02

Brian Hauss

Then she goes to the lawyer and, you know, she's talking about it and what David tells her. And I think this is just a great quote, right? Is I'm telling you, madam, that this is a matter of law. And the truth of your story is irrelevant. We have no knowledge of the story is false. Therefore we're absent malice.

00;13;23;02 - 00;13;51;25

Brian Hauss

We've been both reasonable and prudent. Therefore we're not negligence. We may say whatever we like about Mr. Gallagher, and he is powerless to do us harm. Democracy is served, which is one of those great, extremely cynical lawyer lines that you occasionally get movies like this. And his point is like, yeah, the legal standards not concerned with the truth, the legal standards concerned with what can we get away with and because of the protections, because of the robust protections that the Supreme Court established in New York Times, it turns out that the paper can get away with quite a bit.

00;13;51;26 - 00;14;08;04

Brian Hauss

I think what David tells me give him a call if he denies it, will print that it'll look fair. If he doesn't respond, we can say we tried. And so she kind of halfheartedly calls Gallagher and then immediately goes and prints the story. And actually, Paul Newman later criticized her and said, like, you could have called me back.

00;14;08;04 - 00;14;26;02

Brian Hauss

Riley. She wasn't trying very hard. She was just checking the boxes. She was just doing her job. But she wasn't really concerned. And nobody at the paper seems to be particularly concerned with what the truth actually is with what's really going on. One step behind the scenes they're privy to, they're just pushing right on ahead. And on some level they don't really care who gets hurt.

00;14;26;04 - 00;14;40;25

Brian Hauss

And that's I think you need to go back to your earlier question. When we talk about what the absence of balance means in the title, there's this reference to the legal terminology, the legal terms of art, and there's this reference to sort of what normal people think of as malice. Right. Ill will. And the newspaper's justification here is, look what we have no ill will.

00;14;40;25 - 00;14;57;23

Brian Hauss

We're just doing our jobs. We get information, we print it. He denies it will print that too. We just go ahead and check the boxes and this idea that we can be passive, you know, all of that. And it's not our job to worry about what's going to happen. And that leads to some of the really, I think, excellent debates between Gallagher and Mike later on in the film.

00;14;58;00 - 00;15;12;00

Jonathan Hafetz

It's a great breakdown of the scene. There's one other well, a couple of things I ask you about it in this scene. One is the lawyer, David, who talks about the distinction between or the terms public officials, public figures. How does that play into the standard?

00;15;12;03 - 00;15;30;01

Brian Hauss

So one thing that's important to recognize about the actual malice standard for defamation is it does not apply to everybody in The New York Times versus Sullivan, the Supreme Court said it applied to public officials. So that applies to significant public office holders or people who have positions of significant public trust, including, for example, like police officers. So you don't need to be an elected official.

00;15;30;01 - 00;15;49;01

Brian Hauss

But if the fulfillment of your duties is of significant concern to the public, then the Supreme Court says that people need the ability to criticize you without fear that they're going to be arrested because there are still criminal defamation laws on the books. We actually brought it down to the ACLU, to the Supreme Court. Should all the criminal defamation laws completely, categorically violate the First Amendment.

00;15;49;05 - 00;16;06;10

Brian Hauss

Fortunately, we lost that challenge in the Supreme Court. Didn't take it up. But, you know, criminal liability is one thing that's on the table here. And then there's also the threat of these ruinous civil damages. So the protections of actual malice apply to public officials. But then the Supreme Court also says that they apply to public figures, and that comes from a case Curtis Publishing Co versus butts.

00;16;06;16 - 00;16;22;23

Brian Hauss

And you actually can see a reference to butts in the movie where the lawyer is saying, like, if you were a football coach, that would be great because the law is a little worried about whether Gallagher is a public figure or not. Public figures, when you're talking about public figures, what the Supreme Court said and butts is the same actual malice standard applies.

00;16;22;23 - 00;16;41;18

Brian Hauss

So just because somebody doesn't have elected office in their community or doesn't hold a government job, doesn't mean that the First Amendment protections are implicated, right? Because you can have people who are very important people in the community, right? Big movers and shakers who control the lives of their fellow citizens through, for example, their economic power, even if they don't hold a government job.

00;16;41;22 - 00;17;13;28

Brian Hauss

And so the Supreme Court says, and butts like when you have people of sufficient public notoriety that they're in the news a lot. We need the ability to criticize them in the First Amendment. Protections extend to them, too. So but it was a case about the, football coach at the University of Georgia. And the paper in that case had said that he'd conspired with the coach of the University of Alabama to fix a football game, and relying on a source who claimed to have overheard a telephone conversation between them and the Supreme Court said, in football coaches, if you're if you've ever lived in the South, you know that football coaches are publics of

00;17;13;28 - 00;17;36;12

Brian Hauss

your number one, especially college football coaches in southern communities. And so, you know, the actual malice standards apply to them, just like they apply to public officials. So that's a little reference to if it'd be great if he's a football coach, because then he clearly be a public figure. And similarly, like I think Gallagher's dad, who was like in the movie, is a big time criminal who basically at one time controlled Miami, probably would constitute a public figure.

00;17;36;16 - 00;17;55;21

Brian Hauss

But when you get a little further away, Gallagher's kind of a borderline case, right? He's not a big mob boss. He's the son of a mob boss. Right? And he has this import export business that's basically legit. Not clear that he's a general purpose, what the law calls a general purpose public figure. Speakers also recognize you can have what are called limited purpose public figures.

00;17;55;21 - 00;18;21;25

Brian Hauss

So those are people who are not, you know, world famous or major notoriety in their community, but in specific areas have injected themselves into public controversies. And so they're fair game when the press reports on those specific controversies. So if you participate in a big debate, for example, about a union strike and they're in the papers about it, even if you're not generally a famous person, the actual malice standard replies when the newspapers reported on your participation in that controversy.

00;18;22;00 - 00;18;43;18

Brian Hauss

And that's where some of the controversies around the public figure doctrine have developed over the years. And when we see pushback against the actual malice standard, some of the justices and other critics of New York Times resolve and say, we've expanded it too far so that functionally now it seems like everybody's a public figure. Anybody who, you know, becomes a cancel target on Twitter or something like that becomes a public figure and voluntarily sometimes.

00;18;43;18 - 00;18;57;14

Brian Hauss

And it's free game. You can say whatever you like about that. And is that really right? And so this movie, I think it just touches on that a little bit when it comes to Gallagher, it's like, is he a public figure or not? It's not really clear. And that's the kind of thing where you'd see a lot of litigation over that issue.

00;18;57;17 - 00;19;09;14

Jonathan Hafetz

In the conversation. I think the attorney makes a reference to the uncertainty over who's a public figure, who's not. And if he knew with certainty, you know, he would be very rich man. That's a key thing to know.

00;19;09;18 - 00;19;16;10

Brian Hauss

It's one of the classic ambiguities in the law. And it's what, you know, litigators make. They're not fighting over who's a public figure and who's not.

00;19;16;12 - 00;19;36;18

Jonathan Hafetz

To fast forward towards the end, and we'll come back and pick up some things from the middle of the film. But towards the end of the film, high ranking Justice Department official who's just arrived from Washington, DC, assistant Attorney General Wells, I'm not sure if he has a first name played by Wilford Brimley, gathers all the key players in a room and tries to get to the bottom of things.

00;19;36;23 - 00;19;57;12

Jonathan Hafetz

So he's got Gallagher, you've got Maggie the reporter, you've got the D.A., you've got Balaban, the strike force chief and the assistant who works with him. And this is after the second front page story, the one that Gallagher has engineered, reporting that the D.A. is accepting bribes from Gallagher. Right. It's false, but Gallagher has done that to try to set this up.

00;19;57;14 - 00;20;09;17

Jonathan Hafetz

And so. Well, starts questioning Megan about who told her about the bribery scheme and when the newspapers lawyer objected to Wells questioning, Wells dismisses the objection.

00;20;09;19 - 00;20;11;02

Elliot Rosen

Go ahead, Miss Carter.

00;20;11;04 - 00;20;13;07

Megan Carter

I'm sorry, I can't tell you.

00;20;13;10 - 00;20;15;21

Brian Hauss

I think I know where we're headed here now.

00;20;15;22 - 00;20;22;26

Elliot Rosen

I want to know where these stories come from. Under the First Amendment, my client is not required to reveal her sources. You know that promotion.

00;20;22;28 - 00;20;26;25

Brian Hauss

Under the First Amendment. Don't say that. And the privilege don't exist.

00;20;26;28 - 00;20;27;20

Elliot Rosen

Now, Miss Carter.

00;20;27;20 - 00;20;33;05

Brian Hauss

Do you understand? I can ask you these questions in front of a grand jury. Yes. And if you don't answer, you.

00;20;33;05 - 00;20;34;25

Elliot Rosen

Can go to jail.

00;20;34;28 - 00;20;36;08

Megan Carter

I know it's possible. Yes.

00;20;36;11 - 00;20;37;05

Elliot Rosen

Oh, it's more than.

00;20;37;05 - 00;20;37;25

Brian Hauss

Possible.

00;20;37;25 - 00;20;46;16

Elliot Rosen

Miss Carter. It's damned likely. No, I ain't anxious to be locking up reporters. But I'm going to tell you something, young lady. I don't like what's going on around here.

00;20;46;19 - 00;20;52;27

Jonathan Hafetz

So, as Wells write about the newspaper's lawyers claim of reporters privilege and not having disclosed your sources.

00;20;52;29 - 00;21;18;06

Brian Hauss

So he's right in a limited sense, right? He's right that, you know, the privilege itself is not textually in the First Amendment. And one of the things he's referencing here is the Supreme Court's decision in Brownsboro versus Hayes, which was decided in 1972. That was a case where a reporter had witnessed some drug offenses and was hauled before a grand jury and, you know, asked to disclose his sources for witnessing those offenses.

00;21;18;06 - 00;21;32;22

Brian Hauss

And he said, I'm not going to do that. That was part of my newsgathering activities. I don't have to disclose my sources or what I witness is part of those newsgathering activities, you know, claim protection under the First Amendment. It gets up to the Supreme Court and it becomes a very hotly contested decision and ends up being decided.

00;21;32;22 - 00;21;54;25

Brian Hauss

Five for Justice Byron White, who signed on to Sullivan but in later years became a big critic of the New York Times versus Sullivan regime, writes the opinion I guess you would probably call it a plurality opinion because it ends up breaking down along some lines. But he writes the opinion for the court that basically says, you know, we don't recognize a special right for reporters not to give every man's evidence.

00;21;54;25 - 00;22;15;29

Brian Hauss

So, you know, if the government needs to investigate a crime, you know, reporters can be compelled to testify to a grand jury about what they witnessed. But Justice Powell ends up writing a concurrence where he does say that there should be a privilege that applies here, that kind of evidentiary privilege and what we really need to balance. And there are some an interest at the back of that privilege.

00;22;16;02 - 00;22;34;00

Brian Hauss

And what we need to balance are the government's need for the information versus the harm to the press. Right. Because if you're forced to disclose your sources, who's going to talk to you? Right. If they know that the government, any time they want to call you up and get you to disclose everything that a lot of people who stand a lot to lose by serving as a confidential source, you know, they're not going to do that.

00;22;34;00 - 00;22;55;12

Brian Hauss

And the press's ability to engage in news gathering is going to dry up. And so a power basically says is we have to do sort of case by case process to figure out when reporters can be compelled to testify versus when they can't. And so because four justices end up dissenting in Branchburg, Powells concurrence kind of ends up controlling how courts have read it going forward since Branchburg was decided.

00;22;55;18 - 00;23;16;04

Brian Hauss

I think every federal court of appeals except the Seventh and Eighth Circuits have recognized a federal, you know, qualified at least reporters privilege. Most of them say that that derives in some sense from the First Amendment. Some have also said it derives from the federal common law. And Powells notes, it kind of suggests that it's not a constitutional requirement.

00;23;16;04 - 00;23;48;01

Brian Hauss

You may be suggesting that, you know, legislatures could override it if they wanted to, even if the interests that are at the back of the privilege come from the First Amendment. But in any event, most of the federal courts of appeals have recognized this privilege exists. On top of that, I think 48 of the 50 states and their own laws and jurisdictions have recognized either through statute or through common law decisions by their courts, that either a qualified reporter's privilege or in many states, including California, New York, and absolute reporters, privilege exists so in most jurisdictions in the United States.

00;23;48;01 - 00;24;15;15

Brian Hauss

Now there is a reporter's privilege. And on top of that, and I think this is particularly relevant because this is a DOJ inquiry in the movie in 2021, Attorney General Garland issued new guidelines for the DOJ in terms of when they're going to use compulsory process subpoenas, stuff like that on reporters. And this was in response to revelations that there had been a number of really sort of brazen attempts to use compulsory process against reporters, including by the Trump administration.

00;24;15;15 - 00;24;36;10

Brian Hauss

At the end of the Trump administration that were really shocking. And so, Attorney General Garland says, we're going to put a stop to this, and we're going to implement strong policies to prevent this kind of thing from happening in the future. And under the new DOJ guidelines, when a reporter is engaged in legitimate newsgathering activities, the DOJ cannot use compulsory process against them except in very narrow circumstances.

00;24;36;15 - 00;24;56;12

Brian Hauss

One is when the information's already been publicly reported into. The DOJ is just using the reporter to verify information that's already in the public domain. So the confidentiality concerns are not really present there. And two is when there's like very serious risk of concrete injury to life or limb, you know, major public emergency type things, terrorism, kidnap and stuff like that.

00;24;56;14 - 00;25;18;00

Brian Hauss

I mean, outside of those situations, the DOJ guidelines are pretty categorical in saying that reporters cannot be required to disclose confidential information that was obtained through legitimate news gathering. And on top of that, if there's a question about whether the reporter was engaged in news gathering, basically senior leadership at the DOJ needs to make the call as to whether the reporter was newsgathering or not.

00;25;18;03 - 00;25;36;12

Brian Hauss

So these provide very, very robust protections that I think in the context at issue in this movie. You know, Wells is having this conversation with Meg that that could be right, basically saying, at least as a matter of DOJ policy, you can't force her to disclose that, because that was legitimate news gathering, and it doesn't fall into any of the new DOJ exceptions.

00;25;36;12 - 00;25;43;13

Brian Hauss

Now, of course, that memo didn't exist in 1981. So as of the date of the film, largely accurate but not really accurate anymore.

00;25;43;15 - 00;26;01;29

Jonathan Hafetz

Interesting. So what Wells says she could if you wanted to put her before the grand jury, she refused to answer and then she could be held in contempt. Probably accurate. Then. Not accurate. Now, what's kind of interesting too, though, is Wells. The attorney General does not, by the way. Well for Brummies amazing in this scene.

00;26;02;01 - 00;26;09;22

Brian Hauss

Yeah. Any any movies Walter Brimley is an instant classic. But yeah, this is one of his all time best performances. He like, completely dominates those closing scenes.

00;26;09;25 - 00;26;25;19

Jonathan Hafetz

Utterly. And what really comes across to it could put her before the grand jury. He doesn't want to. Right. There's a sense that he doesn't want to use the full power of the Justice Department, the federal government, to put a reporter before the grand jury at make her testify. I mean, he says he will if he has to, I think.

00;26;25;19 - 00;26;29;09

Jonathan Hafetz

But there's a little bit of kind of bluffing and pressure on.

00;26;29;11 - 00;26;50;03

Brian Hauss

Absolutely. And I think that goes to show. Right. Like on the one hand, he's aware that the press for DOJ, right, enforcing a reporter to disclose this sort of thing in front of the grand jury would not be good. Right? When reporters go to jail for refusing to disclose their sources, you know, that tends to bring down a lot of public opprobrium on the prosecutorial officials who can tell that.

00;26;50;10 - 00;27;20;05

Brian Hauss

So, you know, on the one hand, I think it is a plus on his part because he knows there's would be serious repercussions if he forced her hand on that. And on the other hand, I think it goes to show that, you know, DOJ prefers to resolve most of these things informally. And I think that's probably true in the vast majority of cases, is that even when it has the powers to strong arm reporters and stuff like that, there are lots of other tools short of that the DOJ would prefer to engage in and use, as opposed to going full force in front of a grand jury and sending a reporter off to jail.

00;27;20;07 - 00;27;28;21

Brian Hauss

So I think this movie is kind of accurate in its portrayal of like the strong preference in these kinds of cases is to resolve things in the back room and not to do it in the light of the public.

00;27;28;23 - 00;27;46;04

Jonathan Hafetz

Yeah, that's kind of what happens here, right? Makes us she's not going to reveal the source, although I think well, you know, has an idea of, of what happened. And, and it was a friend who's part of the Strikeforce investigation who told her, tipped her off about the bribes that he thought he was taking to the D.A., but that that is how it resolved.

00;27;46;04 - 00;28;12;29

Jonathan Hafetz

Well, then Wells attorney general says the press has a right to print the leaks. Right? So, you know, he doesn't question the press, right? Or print the leaks. And he turns his anger against the prosecutors for alleging the information. Right. He says, I can't stop them from printing, but I can try to stop the leak. And he really kind of tries to clean house in terms of the strike force, the district attorney on the government side for having, like, set this in motion with leaking the information.

00;28;13;01 - 00;28;24;22

Jonathan Hafetz

What did you make of Welles's recognition of the press's right to print the leaks, and then his effort to kind of really focus on stopping the source of the leaks, rather than really directing the focus on the press for printing the leaks.

00;28;24;29 - 00;28;45;19

Brian Hauss

I think that's where the pressure and an an accurate portrayal of, you know, where First Amendment doctrine ended up going and how DOJ and prosecutorial officials have responded to that case called Bart, Nikki versus Viper. The Supreme Court recognized that the First Amendment protects the right of the press to publish information that was unlawfully obtained or disclosed by a third party.

00;28;45;19 - 00;29;03;11

Brian Hauss

So, you know, in that case, I think it was somebody who had illegally wiretapped union official and had sent it to a reporter. And then this was, people wiretap were suing the reporters for basically saying, like, you knew that we had been illegally taped and you went ahead and publish this thing anyways, and so you could be held liable for the invasion of our privacy.

00;29;03;11 - 00;29;24;04

Brian Hauss

And the Supreme Court said, no, the First Amendment protects the right of the press, at least on matters of public concern, to go ahead and publish things, even if the person who obtained those things did it unlawfully. And so that enshrined a principle that I think even if you go back to the Panama Papers case, right in the Pentagon Papers case, Ellsberg unlawfully discloses the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times and the New York Times, goes ahead and publishes them.

00;29;24;04 - 00;29;42;06

Brian Hauss

The government comes into court, says this is a major betrayal of national security, is is going to cause us to lose the war and endangers American lives. And on that basis, tries to get, prior restraint, I guess the New York Times, an order from the court ordering them to halt the publication of the papers and the Supreme Court says in that case, the one thing we never do is put a restraint on the press.

00;29;42;06 - 00;30;03;12

Brian Hauss

We don't tell the press when to publish. And so we're not going to issue that prior restraint, although they leave open the possibility that maybe there could be criminal liability at stake in one of these things. But I think the the lesson that people took from New York Times was, Sullivan, is that the press does have a right to publish things that maybe should not have been disclosed to it, or maybe should not have been obtained in the way that they were, they were stolen or illegally wiretapped or something like that.

00;30;03;17 - 00;30;20;01

Brian Hauss

And Bart, Nikki comes in and closes the door on that theory and says, the press has a First Amendment right to publish these things, and the government can't say to hold them liable for that. And so when you have that kind of pressure coming from the courts saying you can't go after the press for this, then of course everything turns and focuses on the leaker.

00;30;20;06 - 00;30;38;16

Brian Hauss

And in general, you actually don't see that. I mean, when you consider how many leaks happen in the United States, both, you know, out of the federal government and out of the state governments or prosecutorial offices, leak prosecutions are extraordinarily rare. But towards the tail end of the Obama administration and go into the Trump administration, you started to see a lot more leak prosecutions happening.

00;30;38;16 - 00;30;51;22

Brian Hauss

And that, I think, was the government's response to some of these things, was to say, we're going to stop this, and we're going to stop it by going after the leakers and really throwing the book at them. And there are some pools in the federal government's arsenal to do that if it wants to. And one of the big tools is the Espionage Act.

00;30;51;24 - 00;31;12;16

Brian Hauss

Right. And it says, you know, you're endangering national security by providing classified information to the press. They can really go hammer and tongs on you to do that. And so, you know, in this case, Wells does not pull out the big guns, does not suggest it's going to go down any of those routes. But his focusing on the leakers as opposed to the press, I think, is kind of emblematic about how the government addresses these things.

00;31;12;18 - 00;31;31;16

Jonathan Hafetz

And the context of the film. It's sympathetic, right, because you're the leak was the abuse of government power by Alabama Strike Force chief. This investigation stalled, doesn't know, doesn't really care if Gallagher is involved but knows you know, he has underworld context to his father, probably. And says let's put the squeeze on. I mean, in other situations, leaks play a different role, right?

00;31;31;16 - 00;31;38;25

Jonathan Hafetz

And play an important role. And I don't know, I think the movies as much as about the malice standard, constitutional malice standard. It's about leaks to a little bit.

00;31;38;28 - 00;31;54;21

Brian Hauss

It's absolutely about leaks. And one of the things I love about the movie, and in a way, it's kind of the mirror inverse of, All The President's Men, right? That's a movie on some level about leaks as a form of whistleblowing, which I think is, you know, the popular imagination when we think of leaks, that's usually what we're thinking about.

00;31;54;21 - 00;32;11;18

Brian Hauss

Right? It's some government official who, for various reasons, has become privy to grave misconduct at the highest levels of government and is figuring out a way to get that information to the public so the public can exercise its traditional role of oversight and accountability in the press is an essential part of that. The press has a heroic role to play in that.

00;32;11;21 - 00;32;30;27

Brian Hauss

But, you know, in the day to day leaks, I think often don't look like that. I mean, certainly sometimes they do look like that. Snowden is another recent example of what I would characterize as a heroic leak, as a form of whistleblowing, to inform the public about serious government abuses. but a lot of leaks are actually part and parcel of government policy.

00;32;31;00 - 00;32;55;29

Brian Hauss

And, you know, I would really recommend anybody listening to this David Posner Law Review article, The Leaky Leviathan, is really about the way that the government utilized various sorts of ways to achieve, sometimes individual objectives by the people doing the leaking personal objectives, career advancement, stuff like that, to achieve bureaucratic objectives and turf wars between different parts of the executive branch or the executive versus the legislature, or even broader governmental objectives.

00;32;56;01 - 00;33;13;29

Brian Hauss

You know, the government's own information management system, the classified classification regime that secrecy mandates kind of make it sclerotic, but there is information that it wants for various reasons of governmental policy, to get out to the public. And so leaks enable it to do that informally. And so one of the things that talks about is there's a spectrum.

00;33;14;01 - 00;33;31;05

Brian Hauss

On the one hand, you know, the classic leak is, you know, I think when we think of Deep Throat or Ellsberg Snowden, that's the classic leak. That's the whistleblower acting not just without governmental authority, but in contravention of what the obvious wishes of their superiors in the government would be. On the other hand, you have plants pose basically defiance.

00;33;31;05 - 00;33;52;26

Brian Hauss

These is like when the president or the other like high executive official decides, gives full authorization to give something to the press in order to advance the department's policy in some way, shape or form. But, you know, most leaks, I think, fall in this kind of middle ground gray area. What posing calls leaks, a plant leak, right. Which is where someone is doing something with tacit approval.

00;33;52;26 - 00;34;14;28

Brian Hauss

Right. They're they're going talk to the press. Obviously, their superiors read the papers. They know that this is going on and there's no response. Or maybe there's even subtle encouragement. And those are the, I think, the kind of day to day version of leaks is much more of what you're likely to see is a government official who thinks for various reasons, sometimes individual and sometimes bureaucratic, that it would be useful to get this information in the press.

00;34;15;01 - 00;34;35;26

Brian Hauss

And that's really where Rosen's leak falls. It's a leak, right? He is not doing this to blow the whistle any kind of way. He's not even really doing it for personal aggrandizement. Right. He's trying to basically pursue a DOJ objective, which is to find the guy who killed Diaz, and he's stymied. And so he says, well, one way to do this is we just float a name out there.

00;34;35;28 - 00;34;58;15

Brian Hauss

The press isn't going to care if this person is actually under investigation or not, because they're protected by actual malice standard. So they could just go and print this thing without any fear of liability. And then we can use the pressure that results from that to get more cooperation in our investigation to achieve our objectives. So the sort of informal process that Rosen has, I think, is very emblematic of often how government leaks work.

00;34;58;15 - 00;35;16;25

Brian Hauss

And this is where I think the movie's criticism of the press comes in a little bit, is it suggests and I and I don't think, you know, I think it's important to recognize that this movie is not what a typical reporter would do. Right? You know, Sally Field's character here is really sort of she's a hard nosed reporter, but she makes a ton of mistakes that she violates a lot of very core ethical principles.

00;35;16;25 - 00;35;41;19

Brian Hauss

So this is not emblematic of how normal reporters would think about it, but it is central to the movie's critique, which is sometimes the press is too compliant. It's too willing to repeat what the government tells it without really asking itself why. So I think, you know, what the movie captures is from Post's article. It denotes, you know, the movies made 30 years or 40 years before and wrote, is this notion that a lot of the leaks that come out in the press are cooperative.

00;35;41;19 - 00;36;02;21

Brian Hauss

They're symbiotic with the government. They're not adversarial. The other thing I think that the Wells scene kind of shows also is that and this is also in post article, when the government disapproves of a leak, it's normal. Course of action is not an Espionage Act prosecution. There are informal sanctions that the government can apply. It can shun the leaker, can cut them out of meetings.

00;36;02;21 - 00;36;22;03

Brian Hauss

It can deny them career advancement opportunities. And so that's what you see Wilford Brimley do here, right? He doesn't say we're going to haul all these officials, you know, in front of a grand jury and indict them for serious offenses or obstruction of justice, stuff like that. He basically says to the Da, it's like, well, you know, if I were you, I'd resign because you're going to get a lot of heat from the press.

00;36;22;05 - 00;36;41;07

Brian Hauss

I'm about to give. And he says to Bob Balaban, I'm gonna fire you. Right. Those kind of informal sanctions enable DOJ to keep everything behind the scenes. But the other thing I think that's real interesting to note here is, you know, DOJ does not come in when there are leaks about the case against Gallagher, even though those clearly violate DOJ policy.

00;36;41;07 - 00;37;02;14

Brian Hauss

Right. And Wilford Brimley acknowledges that in the scene. He says, you know, none of these leaks should have happened. But Brimley only comes in when the leaks are interfering with the executive branch, his own objectives. It's only when the leaks are turning on the prosecutors that Bradley's like, this has to come in and stop. And so I think that goes to show the kind of tacit allowance or encouragement that a lot of leakers get from higher ups.

00;37;02;18 - 00;37;22;00

Brian Hauss

It's fine to do it. You know, when it's advancing a DOJ objective, you know, the strike force action in this case, and maybe some people get hurt along the way. Maybe, you know, Gallagher is unfairly pressured, but that's not going to raise the red flags at DOJ that people might disagree with it. What raises the red flags is when you start interfering with executive branch policy and causing the government a lot of embarrassment in public.

00;37;22;05 - 00;37;25;18

Brian Hauss

That's when Wilford Brimley comes out, and that's when the tires hit the pavement.

00;37;25;21 - 00;37;47;10

Jonathan Hafetz

Exactly. Things have blown up and he comes down to clean up the mess. You know, the newspapers have a role to write. They tend not to. The movie suggests, in you know, context of a criminal investigation, affirmatively print something that a suspect has been exonerated. Right. So there's this scene between Sally field, Sally field character, and Paul Newman character on a boat.

00;37;47;12 - 00;37;53;24

Jonathan Hafetz

That's the boat like boater in the movie where he talks about how it's cast a shadow of guilt on an innocent person.

00;37;53;27 - 00;37;58;06

Elliot Rosen

You really think that has something to do with DACA? It's a distinct possibility.

00;37;58;08 - 00;38;00;28

Megan Carter

If there's nothing there, then why are they picking on you?

00;38;01;00 - 00;38;20;22

Elliot Rosen

I got to know where that story came from. Knowledgeable sources. You said, now who is that? Somebody is trying to get to me. Somebody with no face and no name. You're the government. You listen to them, you write what they say, and then you help my. You say you got a right to do that, and I got no right to know who they are.

00;38;20;24 - 00;38;26;10

Megan Carter

I'm sorry, Gallagher, I can't help you. Look, Gallagher, if they clear you all right about.

00;38;26;10 - 00;38;33;22

Elliot Rosen

That, too. But, page, so you say somebody is guilty. Everybody believes you. You say he's innocent. Nobody cares.

00;38;33;24 - 00;38;35;29

Megan Carter

It's not the papers fault. It's people.

00;38;36;02 - 00;38;40;00

Elliot Rosen

People believe whatever they want to believe. Who puts out the paper? Nobody.

00;38;40;02 - 00;38;47;09

Jonathan Hafetz

So the damage is done. They seem not to want to come in and. And we had it wrong. So the newspapers don't want to admit they made a mistake either.

00;38;47;15 - 00;39;02;24

Brian Hauss

I love the fight between on I failed field to see it. I think for me it's actually the climax of the whole movie. And there are two exchanges that I really focused on here. The first is when Paul Newman says, in Sally field, you're the gopher. You listen to them, you write what they say, and then you help them hide.

00;39;02;28 - 00;39;19;18

Brian Hauss

You say you got a right to do that, and I got no right to know who they are. Right. And I think that distills the movie's critique of the press, which is that far from being, you know, this skeptical investigative tool that holds the government to account at every step of the way. Paul Newman saying, like, you're really just stenographers, right?

00;39;19;18 - 00;39;36;12

Brian Hauss

And you don't actually care that much about whether what you're repeating is true or not. Right? They said it, therefore it's news. And therefore I'm going to print it. And then Sally field comes back and basically says, well, you know, if you're cleared when you're terrible, print that too. And he says, like, you know, you print an accusation and everybody believes it.

00;39;36;13 - 00;39;59;00

Brian Hauss

You printed exoneration and nobody's ever even heard of it. And so I feel comes back and says, well, that's not our fault. People believe what they want to believe. And Paul Newman says, who prints the papers? Nobody. And I think what he really nails there is you see this in all the scenes with Meg and Mac and the editorial room, and then Meg and David back in the lawyer's office is they're really kind of removing themselves from any sense of responsibility.

00;39;59;00 - 00;40;20;28

Brian Hauss

They're seeing themselves as passive conduits, like they give us copy, we print it, then we print the next thing that people say in response. And that and that goes out, too. And it's not our job to figure out what's really at the bottom of that. And Paul Newman saying like, no, you have agency here. You can decide whether or not something is newsworthy, whether or not it belongs to go or the public before it's been fully vetted.

00;40;21;04 - 00;40;38;01

Brian Hauss

And that ends up becoming, you know, I would say, like the second climax of the movie, right, is when Paul Newman's friend was with them. When he learns that Diaz was shot because he was taking her to get an abortion in Atlanta, and she wants to keep that under wraps. She wants to keep that secret because she's devout Catholic, goes against the doctrines of her face.

00;40;38;01 - 00;40;56;21

Brian Hauss

She's worried about what her employer's Catholic school is going to do about it. She's worried about what her father is a devout Catholic is going to do about it, and she's personally just very embarrassing, conflicted about sharing that information. But she gives that information to Southfield in a heroic attempt to exonerate Gallagher. And Douglas Blythe is like, oh yeah, we're definitely going to print that.

00;40;56;21 - 00;41;15;26

Brian Hauss

Like people have a right to know that. And when the friend basically says, this is going to destroy my life, Sally field says, people will understand. But she doesn't understand. She doesn't understand that all of the stakes are for this person. And I think, like the devastating scene when you have the newspaper kid going down the street, throwing out the newspapers to the houses, and you see the newspaper land and you don't even notice her at first in the frame.

00;41;15;26 - 00;41;30;14

Brian Hauss

Right? She's just kind of crunched by the door, and she just sort of appears out of nowhere and picks up the paper and the audience is wondering, did Sally feel printed or not? You see her read it, and then she goes and starts picking up the papers off all the other lines and you know, it was printed. And then you find out just a couple scenes later that she commits suicide.

00;41;30;17 - 00;41;40;06

Brian Hauss

And I think that is the indictment of this passive, sort of like someone tells us something that we think is newsworthy. We just go ahead and publish it without kind of regard for the consequences.

00;41;40;08 - 00;41;53;03

Jonathan Hafetz

Such a powerful scene in which Linda Dillon plays the friend, terrific performance and amazing performance. You just watch her kind of go down the street and try to collect the newspapers off the neighbor's front yard. I mean, you can only imagine, like today, right? It would be.

00;41;53;06 - 00;42;05;25

Brian Hauss

It's on Twitter. It's a you know, what it really emphasizes, right? You feel the futility of her action in that moment because, you know, the cast out of the bag can't be put back in and you're just wondering, what are the consequences going to be this when they turn out to be devastating?

00;42;05;27 - 00;42;39;11

Jonathan Hafetz

She reminds me a little bit of some points made in Renata Adler's book Reckless Disregard, which focused on the two high profile defamation suits, one by General Westmoreland against CBS for stories CBS ran accusing Westmoreland of manipulating troop numbers in Vietnam for political objectives and then a suit against time by Ariel Sharon for a story time ran, suggesting what Sharon's role or approval of massacres by the Lebanese Christian militias of Muslims and Arabs in the country.

00;42;39;12 - 00;43;11;06

Jonathan Hafetz

So these were very high profile federal defamation suits and others critical, I think, of the standard of the malice standard. And what she says is, as it's been interpreted, it runs counter not only to reason, coherence and common sense, but also to any conceivable purpose the law is meant to serve. Another interesting sort of subtheme of her book, and I think the movie brings this home, and even in a more powerful way, is that the absence of malice standard or the malice standard, is designed to sort of protect the press from oppression by government officials.

00;43;11;06 - 00;43;30;22

Jonathan Hafetz

Right? To ensure the press vitality with the press is extraordinarily powerful, and you can see that, I think in the movie the power of the press and how, you know, sometimes the press doesn't necessarily always need this protection. Now, of course, it ultimately needs the protection right from the government. But it's a little more complex than this, like underdog press that's in need of the First Amendment protection.

00;43;30;22 - 00;43;34;05

Jonathan Hafetz

And the press can use it. Not so much kind of as a shield, but as a sword.

00;43;34;07 - 00;43;57;06

Brian Hauss

Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I think it's important to recognize that the protections of the malice or the malice standard established in Sullivan have very important benefits, public debate, but they also have real costs. And I think ignoring those costs, pretending that only good and righteous conduct that's protected, that the cost of people's reputations as minimal, that, you know, the press always exercises its role responsibly.

00;43;57;13 - 00;44;15;17

Brian Hauss

I think that sort of Pangloss in sort of optimism is blocked and it fails to address, you know, the very real concerns expressed by the critics of the Sullivan Standard and ultimately it makes the justification for the standard weaker. And so, you know, I think we're not in Adler's book is, you know, one of the all time great trial books.

00;44;15;17 - 00;44;35;23

Brian Hauss

It happens to be written, I think, by one of the best prose stylist of the 20th century for fiction fans. Renata Adler also wrote, like one of the great short New York novellas, speedboat, about a young reporter in New York. And she's just a masterful writer and she's a very, you know, complex and nuanced thinker. And so and she's, you know, assigned to cover these trials.

00;44;35;27 - 00;45;06;29

Brian Hauss

She brings to it a perspective as a reporter and as a lawyer, but also as a person who's concerned about trying to figure out what the truth is, what ethical behavior requires. I didn't read her. Ultimately in the book. And the book is, for one thing, it's a great depiction of two sort of legendary trial lawyers at Cravath, Tom Bar and David Boies, who respectively handled the defenses for time magazine and CVS here, and just how kind of total warfare version of litigation that they practice in defense of their clients.

00;45;07;05 - 00;45;25;21

Brian Hauss

But Adler is ultimately somewhat critical of their approaches in the way their clients approach the cases. And I think her point is sort of that time, for example, to its credit, recognized in its own internal views that the contributor that they relied on for the story about Sharon Halevy was kind of a fabulist and was not a reliable person.

00;45;25;21 - 00;45;47;24

Brian Hauss

And so they understood internally and ethically that this story probably was on pretty shaky ground. But when they're sued, when the matter goes to litigation, the siege mentality sets in and then everything they did has to be justified. As you said earlier, they cannot invent a mistake. And the fear is if they made a mistake at all, that will weaken the First Amendment protections for everybody.

00;45;47;26 - 00;46;14;21

Brian Hauss

So this case, which is ultimately about whether time or CBS, you know, follow the appropriate journalistic practices in leveling these very serious allegations ends up becoming should the military get to dictate what the press prints. And Adler's response to that is the legal questions and the ethical questions are or ought to be somewhat separate. And actually the conflation that's going on is that the press is treating the legal standard as the ethical standard.

00;46;14;23 - 00;46;35;14

Brian Hauss

And in doing that, it's digging in behind positions that are ultimately kind of indefensible. And so even if, you know, Sharon or Westmoreland shouldn't be able to recover as a matter of the correct application of the legal standard in those cases, because I think it's ultimately fairly clear that there was not genuine actual malice on the part of time or CBS when they published the stories.

00;46;35;16 - 00;46;56;08

Brian Hauss

The question of whether it was right to do it kind of gets lost in all the shuffle, and Adler is relentless in bringing that back to the fore and saying, like, you know, if we're really trying to figure out what the truth is and if we're really concerned with the ethical practices of journalism are you have to distance yourself a little bit from the kind of low bar that the Supreme Court intentionally set by the actual malice standard, and focus on other things.

00;46;56;08 - 00;47;14;28

Brian Hauss

And I think, as you say, that there is really well with this film because the film is makes a kind of a similar argument. Is the press doing what it can get away with in the movie and not necessarily what it should be doing. Now. Again, like I think, you know, as with the movie, I don't think what CBS and time did in those cases is necessarily emblematic of regular practices by the press.

00;47;14;29 - 00;47;35;07

Brian Hauss

These are cases of some degree of misconduct, but it's important to keep in mind the possibility that those things can happen and that actually some degree of self accountability for the press is important in order for public support behind the legal standards to continue. And so, you know, if the press doesn't successfully police itself, eventually the legal standards are going to change.

00;47;35;13 - 00;47;50;03

Brian Hauss

Right? And that's, I think, some of the pressure we're seeing now in response to of it. I don't think all of that is really in response to the press falling down on the job. It's in some sense in response to changes in how media is distributed. But I think the notion that the press doesn't police itself, the law was going to police.

00;47;50;03 - 00;47;56;27

Brian Hauss

It is still an important one to keep in mind. That's why I think it's so important to wrestle with critics like Renata Adler and Sydney Pollack.

00;47;57;00 - 00;48;21;11

Jonathan Hafetz

In the press itself has changed. It's Brian, right? I mean, we're long beyond the kind of Cronkite era, what we might call more responsible journalism, right, where you have so many different outlets. And then the dissemination through social media is just as scale. Unimaginable now just ended with a quote from Justice Gorsuch, who along with Justice Thomas, you know, one of the sharpest critics on the court of the New York Times was Sullivan Standard and has called for this to be reexamined.

00;48;21;11 - 00;48;57;02

Jonathan Hafetz

And what Gorsuch said in one of his separate opinions, what hasn't taken up the Gantlet yet, but what he said was the actual malice doctrine might have made sense when there were fewer and more reliable sources of news, dominated by outlets employing legions of investigative reporters, editors and fact checkers. But he continued the court's decision. In 1964, New York Times versus Sullivan to tolerate the occasional falsehood to ensure robust reporting by a comparative handful of print and broadcast outlets, has evolved into an ironclad subsidy for the publication of falsehood by a means on a scale previously unimaginable.

00;48;57;04 - 00;49;15;18

Brian Hauss

With all respect to Justice Gorsuch, I think that's a little overheated. in a couple of ways. I mean, first, I think this notion that the actual malice standard was invented by the Supreme Court out of whole cloth in 1964 is kind of a red herring, right? It is true that as a matter of Supreme Court First Amendment doctrine, that is when the actual malice standard is established.

00;49;15;23 - 00;49;42;17

Brian Hauss

But in fact, the court is drawing on common law developments in the state courts up through 1964 that had protected things like fair comment and stuff like that. So there's actually a long and robust development in American law of this notion that the press necessarily has a lot of room to comment on public affairs and that really, again, goes back to Madison's remonstrance, where, you know, he says the whole foundation of the country is the ability of people to criticize public officials.

00;49;42;21 - 00;49;58;11

Brian Hauss

And I think public figures is a necessary part of that, free from the fear that they're going to be hauled in if somebody doesn't like what they have to say. And part of the problem here is when you're dealing with matters that go to the heart of public controversies, public policy, the truth is going to be a very, very contested thing.

00;49;58;16 - 00;50;15;26

Brian Hauss

And so the question is, at what point do we want the law to come in and punish speech? That goes to the heart of public debate. You know, what kind of breathing room are we going to protect around that? Even long before Sullivan, American courts and legislators recognize the need to provide that sort of breathing room for the press.

00;50;15;26 - 00;50;39;07

Brian Hauss

And you see that, for example, when Jefferson says, essentially, right, the, you know, the press may abuse its powers a lot, but at the end of the day, I would rather have an irresponsible press, the no press at all. So I think the history and the foundation of that is wrong. But I also think this notion that in response to changes in the media environment, and I think it's also important to recognize that the media environment that existed in 1964 is an anomaly historically.

00;50;39;07 - 00;51;01;15

Brian Hauss

Right. That wasn't true of the United States. Most journalists in United States, before, you know, the middle of the 20th century, was the kind of yellow journalism that Gorsuch decries, right? The people who are getting prosecuted in this edition at controversy and these were clearly Partizan aligned newspapers that were publishing vicious attacks on their party opponents, and probably themselves were not especially concerned with the veracity of what they were saying.

00;51;01;15 - 00;51;24;16

Brian Hauss

But the view of the press that was this is an important part of just how public debate plays out. Even if they're party organs. This is an important part of how people hear from all sides, hear these even very biased views, and then come to a conclusion. And this notion that the press has this objective view from nowhere thing was something that I think arose as a result of consolidation of the press and certain developments and ethical standards in journalism in the middle of the 20th century.

00;51;24;22 - 00;51;45;17

Brian Hauss

But we existed with the free press when those conditions didn't exist and will exist even if those conditions disappear. I think Gorsuch also undervalues the danger posed by defamation lawsuits. Any, you know, kind of supposes that every defamation plaintiff who comes in is going to be someone who suffered a very serious wrong to their reputation on the basis of something that's blatantly false.

00;51;45;19 - 00;52;09;09

Brian Hauss

But we know from experience that that's often not what happens. You have lawyers call strategic lawsuits against public participation or slaps is basically when a powerful individual or corporation sues their critics for defamation or another similar type of offense, not expecting to win anything, not because they think they have a strong legal claim on the merits, but because they know that they have the financial resources to do scorched earth litigation.

00;52;09;11 - 00;52;32;01

Brian Hauss

Their opponent maybe does not. And that's going to be especially true, I think, in today's media environment. A lot of independent press organizations are operating on shoestring budgets and razor thin margins. And so defending those kinds of drag out lawsuits, even if they're borderline frivolous, is going to be cost prohibitive for a lot of institutions and individuals. And so if you weaken the malice standards, right, if you make it easier for those things to get to a jury, right.

00;52;32;01 - 00;52;48;22

Brian Hauss

Questions and negligence, stuff like that, classic jury questions, the press is going to be afraid to print a lot of things that are true because they're still going to face the potential to be hauled in front of potentially also a biased jury by a powerful individual who doesn't like what they have to say. And, you know, even if you just look at the cost of insurance, right.

00;52;48;22 - 00;53;21;14

Brian Hauss

If you got rid of the actual malice standards, liability insurance for live on stuff like that's going to go way up, that can bankrupt a lot of news organizations that are just hanging on by a thread right now. So that's my first point. And my second point is I think courts also benefit from the actual malice standard because at the end of the day, you don't want courts deciding the truth of some of these controversies because they're so fraught that, you know, political passions on either side are so high, the truth is so murky and complex and hard to discover that requiring a judge to discern the truth of it, you know, puts the courts

00;53;21;14 - 00;53;49;08

Brian Hauss

in a very awkward position, and the courts benefit to some degree. And this goes back to what David says to me in the film. I don't care what the truth is. My question is whether there's mouths right. Did you have strong reason to doubt what you published? And so that makes the job a lot easier for courts, because it basically says in the clear cut cases where there's something was obviously wrong and there's blatant misconduct by the reporter, by the newspaper, there's a role for courts to step in and impose liability in those circumstances.

00;53;49;08 - 00;54;03;14

Brian Hauss

But in those borderline cases where the truth is really hard to decide, we let the public decide what the truth is, and we don't force the judicial process into those conversations. And ultimately, I think that's a more democratic answer to the problems posed by misinformation.

00;54;03;16 - 00;54;11;06

Jonathan Hafetz

And the film itself seems to be saying, right, the press should behave more ethically, more consciously, right? And the government should do the same with its leaks.

00;54;11;08 - 00;54;34;22

Brian Hauss

Yeah. I mean, I think that's kind of Wilford Brimley point, right? And he's sort of the the moral compass of the movie. And he says to Meg, right. You know, we hope you'll act responsibly, but there's not a lot we can do about it when you don't. And he recognizes that it's important to limit the government's ability to respond when the press doesn't act responsibly because of the concerns about abuse of power, about censorship that would be implicated if it did.

00;54;35;00 - 00;54;44;01

Brian Hauss

So it's really on the press to police itself. It's not the government's role. In many cases. It shouldn't be the court's role to exercise editorial judgment instead of the press.

00;54;44;03 - 00;54;57;17

Jonathan Hafetz

Well, Brian, thanks so much for coming on the podcast and sharing your vast knowledge of the First Amendment and your insights into this movie, which I still think holds up well. I mean, it's a really important reminder of kind of the issues we've been talking about.

00;54;57;19 - 00;55;16;16

Brian Hauss